Fair Dealing

February 28, 2022, by Steacy Easton

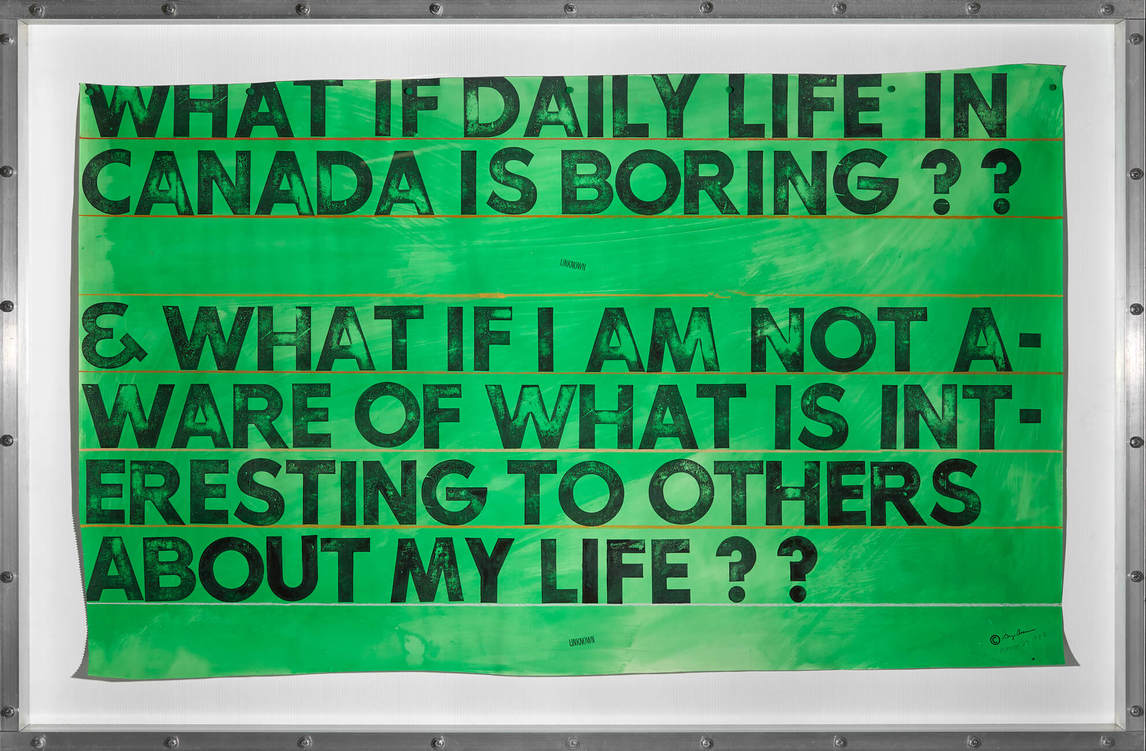

Greg Curnoe, Doubtful Insight, March 23, 1987; gouache, watercolour, stamp pad ink, pastel on wove paper; 117.8 x 190.5 cm; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

- I always thought that I would go back to Toronto, but after 4 years in Montreal, and 6 years in Hamilton, I now know I never will. Last month, my best friend moved to Halifax, and he was my last strong tie. A year of lockdowns and stay-at-home orders forces you to stay put. I have been thinking for a while about what stability means after moving apartments every eight months and cities every five years, and those thoughts return again to the local--what my house is composed of, what my neighborhood consists of, what my city resembles. I am reminded of Greg Curnoe, the printmaker, painter, and archivist who went from being interested in the nation, to his city (London, Ontario), to his neighbourhood, and finally to his own backyard.

- In the mid to late 1970s, Canada was very anxious about what it meant to be Canadian, where artists and critics pushed against the colonial heritage of the United States and England. It was nationalism, but perhaps not patriotism. In 1972, Greg Curnoe made a screen print, where Mexico abuts Canada, literally excising America. In 1988, in the middle of conversations about NAFTA, and Mulroney-led neoliberalism, he made a series of prints of sayings (See a 1988 text piece, consisting of the words, “As A Patriotic Canadian, I respect and honor the priorities of our American Comrades”) about how the prime minister literally sold Canada to the greatest interests. Between the 1970s printmaking, and the 1980s Mulroney baiting, he told the tweedy Canadian journalist Alan Forthigham: “My work is about resisting as much as possible the tendency of American culture to overwhelm other cultures.” He did that by not only making work and writing manifestos, but traveling throughout Canada, advocating for the material support of Canadian visual artists. 1

- Canada is abstract as a nation state, disorganized, and fractious. It seems significant that Curnoe was working through what it meant to make Canadian work, when post-centennial no one knew exactly what Canada meant. In a fervour of identity making, being a colonial subject was not enough. This was the era of Marshall McLuhan and Northope Frye, of Leonard Cohen docs funded by the NFB, of the Joyce Weiland film Rat Life and Diet in North America where the diet is an American flag, or her bronze sculptures, of a woman fucking a bear, of two beavers suckling the spirit of Canada – one of the beavers French, and the other English.

- Curnoe was never really scandalous or academic, but he had his moments. 1965’s Three Pieces, a two-sided triptych of Canadian history, featured a giant portrait of Louis Riel, in a pop psychedelic style, alongside pasted notices of Canadian students meeting Cuban revolutionaries. He painted major commissions, including one for the Dorval airport in Montreal that was taken down in an act of censorship due to its references to the Vietnam war, and Canada’s complacency. His 1967 sculpture/painting/portrait of William Lyon Mackenzie, has the figure surrounded by text of how the CCF Liberals and Tories specifically betrayed Canada. There is something ambitious about these large pieces.

![]()

![]()

Greg Curnoe, 24 Hourly Notes, December 14–15, 1966, stamp pad ink and acrylic on galvanized iron; 24 panels, each 25.4 x 25.4 cm; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

- I think his bravest move was shifting away from the monumental. The second most famous censorship controversy of his career involved a set of drawings called 24 Hourly Notes, December 14–15, 1966. Printed with a handmade rubber stamp on small paper---blue on blue, orange on orange, black on white, graphically involved-- they depict both the sublime and banal of what occurred on that date: he gets out of a truck, he greets friends, he makes work, and he listens to jazz. In it, he describes one of the jazz players “holding his horn like a prick.” The work was pulled from a show in Edinburgh, and it ended up in an Ottawa show that Trudeau et père was at. For all of his sins Trudeau had good taste, and though the work was taken down in Edinburgh, it was not taken down in Ottawa.

- There is this narrative of Curnoe, that his work got smaller, more intimate, and personal the older he got. In thinking about being stuck in the same place for so long, as the world tightens, and the anxiety spikes, I’ve begun to think that the local and the global are a false dichotomy. As he progressed, Curnoe became less Canadian, less interested in Canadian work and more interested in his hometown of London, but as a way to conceptualize, deepen, and widen what landscape can be. Landscape is an explicit reference to moving in space, a notice that someone has been there, noting human interaction with a specific material location, a colonial claim. Curnoe’s friend and fellow painter Jack Chambers's photorealistic, eerie depictions of airports and highways are landscapes, perhaps more traditionally, though they depicted pieces of Canadian banality that marked the ambition of mid-century infrastructure development. Curnoe's work in London was close to the ground, of the bicycle touring which would eventually lead to his death, and, in some of his earliest and best work, of framed and positioned bus transfers.

![]()

Design for Curnoe’s centennial cake with text based on “Wild Thing” by The Troggs, c.1967 Pencil on paper, collection of Stephen Smart

- The conceptual work was diaristic, in the most obvious sense. I was there, and then I was there--as diaristric as his twenty-four-hour notes, as funny as his reducing the entire 300 year history of Canadian art, to a one liner from the garage band the Troggs (ie 300 Years of Canadian Art, I Think I Love You/300 Years of Canadian Art I Think I Need You), and as loving as his endless depictions of bicycles. His conceptual turn would lead to his most significant work. It seems significant that when he became successful, he moved to a house near the Thames. Next to the house was his studio. After he died, his wife covered the small laneway between the home and the office, but even before that, the domestic and the artistic slid into each other--children were raised, politics were argued, works were written in a space with little separation. Curnoe moved from depicting the city, to the home, but the domestic became another form of creation.

- The studio for Curnoe was a home business. He wanted his work to be successful enough to pay for that comfortable domestic space. The studio/house he bought was a 19th century space, but it was always used as a printing studio--as he says, later on, quotes in Henry Godden’s review for the project in Brick Magazine: He explains:

Our building was built in 1891 by Thomas Knowles senior [1841 – 1926]…as a lithography shop for his sons Thomas [1866 – 1933] and Joseph Knowles [1868 – 1954]. London artist Albert Templar apprenticed here in 1917. He ground litho stones as part of his apprenticeship…My son Galen and I have dug up Knowles Company litho stones from the back of our building. My most recent prints were three editions of lithographs, drawn directly onto litho stones. The lithographer/owners who worked here were well connected socially to the extent of belonging to the exclusive Forest City Bicycle Club…The Knowles brothers rode their bicycles from 38 Weston Street to their club rides. I leave from the same place for club rides with the London Centennial Wheelers.

- Curnoe died young, the victim of a cycling accident 20 minutes from his home and studio. In the time between settling into this new space and his death, he made an extensive book work about the property’s history, called Deeds/Abstracts. His goal was to write about everyone that occupied the land where his studio was, ending at 8600 BCE, with a depiction of “small, mobile groups of hunter-gatherers live around London in camps.” Stacy Ernst, in her long essay comparing Curnoe and the Indigenous printmaker Carl Beam, talks of Deed/Abstract as “signaling their (the books) position as another aspect of an unfolding history rather than as the beginning of the story.”

- As an act of research, it’s a complex, unsettled document, Curnoe quotes competing narratives, compounds a variety of stories, attempts to work out exactly what happened in that space--and unlike the post colonial conceptual/ ideological work from the 1970s, refused a singular ideology. I wonder when we do land acknowledgements, the careful, quiet noting of lineage and space, denies the complex history of a space, and westernizes Indigenous cultures of space and time.

- When Canadian art history talks about local spaces, and about the domestic, and about what was there before, it is a very white history (see Kurelek or Mary Pratt). With Curnoe’s London, it is even more than that, a very English history. Like history began in 1891. For all of the class-recognition that printing was a craft for a very long time, more like making bricks or brewing beer than making art, the desire to archive, to own land, is a colonial practice. Ernst quotes the Maori scholar, Linda Tuhiwai Smith: “coming to know the past has been a part of the critical pedagogy of decolonization. To hold alternative histories is to hold alternative knowledges. The pedagogical implication of this access to alternative knowledges is that they can form the basis of alternative ways of doing things.”

![]()

Greg Curnoe, Deeds #2, January 5, 1991–January 7, 1991 Stamp pad ink, pencil, blue pencil, and gouache on paper 108 x 168.9 cm Private collection

- Curnoe’s history becomes more and more unsettled--the erasure of the United States, becomes an ignoring of the nation at all; an interest in western history, over time, becomes an interest in the domestic, but that history of the domestic moved from the general and theoretical, to a very specific house in a very specific neighbourhood, in London. A nation becomes a city, a city becomes a neighbourhood, a neighbourhood becomes a single house, and a single house becomes a network of interrelated humans and undefinable selves. History slips away, reasserts itself. Thinking about his sources, he is more likely to trust an archive, he doesn’t talk to elders, but is he doing the work within his own context.--Is recognizing the long-standing history of a land that he claims as his own the beginning act of Indigenizing his own space? If that's the case, will he give up what he has worked for? When does the need for the domestic, and the need to indigenize these spaces, begin to address the need for reparations? Curnoe’s ideas of the local are haunted by settler colonialism, and violence done against indigenous peoples, and how they collect/distribute information-even his interest in indigenous spaces, were fostered by a white anthropologist studying pictographs. So, Deed/Abstract is a beginning, but one that fails because of its reliance of white knowledge systems, on colonial ideas of the local.

- I am writing this at the corner of Picton and James. two streets named after western colonizers. I am in an apartment that was built in 2020. I have lived in 29 houses in twenty years--dorms and rented rooms mostly. I keep thinking about Greg Curnoe, partly because of this problem of the domestic and the local--how do we make small lives and small work, how do we avoid the monumental, how do we know ourselves and the places we live? I am also thinking of a text piece he did in the middle of the NAFTA years in his classic rubber stamp stencil on a green field that says: “What if Daily Life In Canada is Boring? & What if I Am Not Aware of What Is Interesting About My Life?” What if daily life is boring, and what if careful consideration of the boredom, brings you away from Canada, towards your own backyard? What if that stability lets you make a great work of observation, and what if that great work, interesting despite (or because of) its boredom, allows the observer a new way forward, perhaps one which prioritizes the complexities of your immediate surroundings, with care?

Footnotes

1. He was instrumental in the foundation of Canadian Artists’ Representation/Le front des artistes canadiens (CARFAC), a visual arts organization, which advocated for things like minimum fees for exhibitions.

Steacy Easton is a writer and artist, currently living in Hamilton. They are interested in the intersection between class and sex, and visual cultures outside of traditional designations of “fine art”.

Instagram: @pinkmoose4eva

Twitter: @pinkmoose