Interview with the Curator: III at the Art Gallery of Regina

July 8, 2025

Hooria Rajabzadeh interviews curator Sandee Moore about the exhibition III at the Art Gallery of Regina. III featured the work of Deborah Potter, Leesa Streifler, and Sheila Nourse, and ran from January 23 to March 29, 2025.

Installation view of III at Art Gallery of Regina, 2025. Photo: Don Hall.

Installation view of III at Art Gallery of Regina, 2025. Photo: Don Hall.How did you navigate curating without flattening or generalizing the artists' voices under a unifying narrative about aging and womanhood?

SM: Actually, my approach is always to start with the artist and the artwork. I don’t begin with an idea for an exhibition and then find artists to fit into it. Instead, I do a lot of research, which includes studio visits, looking at artworks, and talking to artists. From that process, I begin to form ideas for exhibitions.

Over the last few years, during studio visits, I noticed that many artists—especially women—have been making work about aging and caregiving. Often, these women are having a dual experience: they are postmenopausal themselves, and at the same time, they are caring for their elderly parents in their final years. They are creating artwork about those experiences.

Because I saw that happening, it gave me the idea to put together an exhibition on this theme. I believe both of these experiences—aging and caregiving—are difficult, and that we can understand and process them differently. Sometimes, all people want to know is that they are not alone in these experiences. That’s part of what art can offer—connection, empathy, and recognition.

That’s how I came to the idea for the exhibition, and I always want the artist's voice to come through. I very deliberately selected artists who approach the topic of aging and elderly women from very different perspectives. That’s also one of the reasons I like to curate group exhibitions—because they allow for many facets of an issue or experience to be explored through different artists’ works.

For example, Leesa Streifler work in the exhibition III was largely inspired by her experience caring for her elderly mother, as well as her reflections on her own aging body. In contrast, Sheila Nourse’ work focused on celebrating women over 50 who had made a difference in her life and in the world. What interested me especially about Sheila’s perspective—particularly in terms of representation and identity—was that she didn’t create images of what these women looked like. Instead, she created assemblage sculptures made from items and materials that represented the things these women cared about, the activities that gave their lives meaning.

These sculptures became almost like archaeological artifacts—evidence of a life lived, accumulated through time. That way of representing aging and experience was deeply moving and offered a very different approach from the others in the show.

Golden Salon Series detail: Purple Warrior (Judy), Sheila Nourse, mixed media, 12.5 x 18.5", 2024. Photo: Don Hall.

Were there any moments in your curatorial work, when you choose to withhold interpretation to allow ambiguity, or even discomfort, to remain in the encounter between viewer and artwork?

SM: Yeah, that’s an interesting question. Certainly, my feeling—or my approach—is that I don’t want to force my interpretation onto anyone. I don’t want to impose it on either the artist or the audience. For the artist, their work may mean something different to them, or the goal they have in communicating it may differ from how I interpret it. And with the audience, I want to leave space for their own interpretations as well.

I think my approach is to offer different levels of engagement. If people want more, they can easily access it. For example, at the gallery, I write an exhibition didactic panel that is under 300 words. It provides an overview—just the big, overarching idea of the exhibition.

Then, we have a self-guided tour pamphlet, which includes three or four questions that point out one or two individual works. For example, one of the questions in the III exhibition focused on how the artists use scale differently. Deborah’s work consisted of miniature sculptures, which made us sense the vulnerability of older and elderly people. Leesa Streifler’s works were enormous, evoking the power and presence of women who, although often disempowered, can still have a huge impact through their actions. So that’s another layer of interpretation we offer—optional and open-ended.

The final level is the exhibition’s audio tour, which guides people through each artwork in more depth. Even with that, my approach is to ask questions and help viewers understand how to interpret a work of art, rather than telling them what it means. The example I gave from the self-guided pamphlet is a good one—we start with questions. We explore how artwork can mean more than just what it represents. Elements like the material, the artist’s choice of medium, the scale, the composition—whether it’s tidy or messy—all contribute to the feeling or "vibe" of the work.

People can often sense the artist’s intention, even if they don’t consciously articulate it. For instance, they may not say, “She used a small scale to make me feel this figure is vulnerable or insignificant in society,” but they will start to associate things with smallness. In Deborah’s work, her choice to use ceramic figurines brings up associations for many people—familiar, fragile, domestic—and that contributes to their personal interpretation.

H: So it’s like you give the audience the tools, and you leave the interpretation to them?

SM: Yes, my ultimate goal is to give people the tools to interpret artwork for themselves using the elements of art. That’s one of my real pleasures as a curator—to help people discover that art can have meaning in their lives and resonate with their experiences, so that they can understand it. It’s not an elite activity.

Installation view of III at Art Gallery of Regina, 2025. Photo: Don Hall.

Installation view of III at Art Gallery of Regina, 2025. Photo: Don Hall.How did you curate a “conversation” between the artists’ works without dissolving their individual voices? How did you create a conversation between each artist's work and artwork?

SM: Again, that’s one of the things I feel so privileged to do. Of course, I always consult with the artists. I tell them, “I want to curate your work in a show with this person and this person—this is what their work is like, and this is why I’d like to bring your works together.” But I also do a lot of hands-on installation myself, putting the work up in the gallery, and that’s really beneficial.

In the exhibition III, that hands-on process was particularly fun and beneficial for the overall show. As we were installing, we started with the works that went on the walls. We hung Leesa Streifler’s enormous drawings, and then, on almost the opposite side of the gallery, we placed Sheila Nourse’s assemblages. Then we brought in Deborah Potter’s sculptures.

There was this moment where one of Leesa Streifler’s drawings featured a woman wearing a pair of high-rise pink panties—you know, what we used to call “grandma panties.” Deborah had a sculpture of a woman with gray hair wearing a similar pair of pink panties. We just said, “These two women have to be looking at each other.” So we placed them deliberately to create that dialogue.

There were other instances too—moments where the subject matter created a shared experience between artists. For example, those high-waisted underwear became a kind of symbol of aging femininity—maybe even of post-menopausal sexuality, and how it changes or is perceived to diminish.

Big Girl Panties, Deborah Potter, Clay and glazes, 14"x3.5"x3.5", 2024. Photo: Don Hall.

Other conversations happened through visual elements. There was a large drawing by Leesa Streifler called Waiting, and we placed three of Deb’s sculptures nearby. They weren’t directly in front of it, but from certain angles in the gallery, you could see the sculptures—which were in dark red, orange, and gray—and they beautifully complemented the colors in Leesa Streifler’s drawing. So, color relationships also helped shape these visual conversations.

There were also material echoes. One example was a shared use of similar items—Deborah had a sculpture where the figure was wearing knitted socks, and Sheila had knitting needles in her assemblage work. It wasn’t just the literal material—it was the symbolic significance of those objects. Sometimes, one artist might present something in a way that reads as weak or vulnerable, while another presents the same symbolic item as a source of power, satisfaction, or personhood.

I think the knitting needles in Sheila’s work are a great example of that. Knitting is often seen as symbolic of an older woman—maybe someone just keeping her hands busy. It’s rarely seen as something powerful or meaningful. But Sheila stuck knitting needles through a picture frame in one of her assemblages, and I just thought it was such a funny, bold gesture. To me, it was like she was “stabbing” the picture frame—a symbol of the traditional art world, one that often excluded women and dismissed art practices considered “women’s work.”

It was humorous, but also very powerful. The picture frame traditionally says, “This is art,” and here she was, disrupting that with something associated with domesticity and craft. It really felt like a rebellious gesture—“sticking it” to the institution that devalues these forms. That’s one of the things I loved about including her work. So many people get dismissed, excluded, or diminished for so many reasons, and these pieces directly addressed that with both wit and strength.

Installation view at Art Gallery of Regina. (Left to right) Stop, Leesa Streifler,Gouache and chalk on pastel board, 9"x12", 2014; Chakras, Leesa Streifler, Pen and watercolour on board, 7"x5"; Her Body, Leesa Streifler, Mixed media on vintage leather gloves, 2020. Photo: Don Hall.

Installation view at Art Gallery of Regina. (Left to right) Stop, Leesa Streifler,Gouache and chalk on pastel board, 9"x12", 2014; Chakras, Leesa Streifler, Pen and watercolour on board, 7"x5"; Her Body, Leesa Streifler, Mixed media on vintage leather gloves, 2020. Photo: Don Hall.

The artists use domestic and craft materials—ceramics, textiles, assemblage—long associated with “women’s work.” Did this material language shape your curatorial thinking in terms of reclaiming or redefining those associations?

SM: I wouldn’t say that I was specifically trying to program artists who were working in mediums that had previously been dismissed as “women’s work” or excluded from fine art because they were categorized as craft. But I am often interested in including a range of different art practices in an exhibition. I love bringing in works that might not match what people typically picture when they think of “art in an art gallery”—to challenge those preconceived notions.

Certainly, one of the things that was very satisfying for me in this exhibition was including practices that some might not immediately think of as fine art. Sheila’s assemblage work is a great example. Not only is she working in a material language that has historically been devalued, but she’s also over 65, making work about the experiences of older and elderly women. That in itself feels really innovative and, to me, challenges the status quo of what is considered “legitimate” or “high” art.

So yes, including practices like assemblage or ceramics—materials and methods that were previously excluded from galleries—was something I found very satisfying, even if it wasn’t my initial curatorial goal. These choices help expand people’s understanding of what art can be, and whose voices and materials deserve space in a gallery.

Installation view at Art Gallery of Regina. Golden Salon Series (details from left to right: Stone Path (Loretta), Treasure Hunter (Margaret), Purple Warrior (Judy), The Promise (Rae)), Sheila

Nourse, mixed media, dimensions vary, 2024. Photo: Don Hall.

Installation view at Art Gallery of Regina. Golden Salon Series (details from left to right: Stone Path (Loretta), Treasure Hunter (Margaret), Purple Warrior (Judy), The Promise (Rae)), Sheila

Nourse, mixed media, dimensions vary, 2024. Photo: Don Hall.

Assemblage seems to function as a metaphor for self-construction in life. Do you see this reassembly of broken or discarded materials as not just aesthetic, but also a political or survivalist gesture—aligned with feminist strategies of repair and resilience?

SM: I think you really hit the nail on the head there. That’s a really astute and insightful reading of assemblage as a practice. I think that’s one of the things I find so compelling about it.

Sheila’s studio is incredible—it's floor-to-ceiling shelves with bins of things that she collects, all of which she plans to use one day in her artwork. They’re all items that have been broken or discarded. So, as I mentioned before, she’s building up this portrait of a woman through the things that give her life meaning—the activities and objects that reflect her impact in the world.

But beyond that, the idea that just because something isn’t perfect, whole, or new doesn’t mean you can’t use it to build your identity—that’s really powerful. In fact, lots of people have fractures in their lives—relationship breakups, traumatic events, or other negative experiences—and all of those contribute to the whole person.

So yes, I think your interpretation is perfect. Assemblage, in this sense, isn't just aesthetic—it is also deeply political and survivalist. It aligns beautifully with feminist strategies of repair and resilience.

Deborah Potter’s figures seem to resist gendered markers. Some resemble children or men. Was this ambiguity part of your curatorial framing, and how does it complicate or expand the show’s treatment of aging as a gendered experience?

SM: I think that wasn’t really part of my curatorial framing, but more about letting the artist have their voice and express what they want. That kind of ambiguity is definitely something we see in Deb’s work very deliberately. As I mentioned before, by making these really small, miniature ceramic figurines, she’s showing us the vulnerability of the elderly.

Also, when a woman goes through menopause—when she stops menstruating, ovulating, and having children—there can be a kind of decline in sexual characteristics. So there’s often a less gendered identity associated with older people. And I think that’s part of what Deb is exploring—how aging can diminish not only gendered expression but also a person’s agency.

Some of her work comes not from her own lived experience but from witnessing her mother, father, and other family members in the later stages of life, when they may no longer be capable of doing things like dressing or feeding themselves. In that sense, they begin to resemble children again.

Isolated, Deborah Potter, Clay and glazes, glass cylinder, 12"x7"x7", 2024. Photo: Don Hall.

One of her pieces was very deliberately based on something she saw while visiting her mother in a care home. She looked into an empty room, and on top of the bed was a doll. That image really struck her. It offered such a profound insight into what that experience might be like for the person living in that room—seeking the kind of comfort we associate with childhood, or perhaps reliving a nurturing role by caring for the doll. It speaks to both a regression and a reclaiming of meaning in later life.

I think it's also important to note that all of the artists in the exhibition are women, and they are making work based on their own experiences. Leesa Streifler, for example, told me about one of her drawings—a portrait of her and her husband. She mentioned that this was the only man depicted in the exhibition. But even then, she titled the work to reflect that he is sort of an appendage to the woman, reversing the usual societal framing of couples where the male partner is often seen as the central figure.

The image itself isn’t overtly romantic, but it conveys something very tender and moving—a sense that they are in it together. That shared experience, rather than traditional gender roles, is what really comes through.

Installation view at Art Gallery of Regina. (Clockwise from top left) Old Bird, Deborah Potter, Clay and glazes, 16"x5"x3.5", 2024; Freedom 55, Deborah Potter, Clay and glaze, found object, 15.5"x7"x6", 2024; Invisible II, Deborah Potter, Clay, glazes, 6 x 6 x 7”, 2024. Photo: Don Hall.

Installation view at Art Gallery of Regina. (Clockwise from top left) Old Bird, Deborah Potter, Clay and glazes, 16"x5"x3.5", 2024; Freedom 55, Deborah Potter, Clay and glaze, found object, 15.5"x7"x6", 2024; Invisible II, Deborah Potter, Clay, glazes, 6 x 6 x 7”, 2024. Photo: Don Hall.

Leesa Streifler’s large-scale works seem to reclaim space for aging women’s experiences. Can we read this as a counterpoint to Deborah’s miniatures—a tension between shrinking and expanding presence?

SM: I think certainly, as we’ve talked about before, scale plays an important role. Leesa Streifler is making these women oversized—making us notice them, making us maybe recognize that they have power. While Deb’s sculptures are tiny and made of ceramic, and some of them explore a loss of independence or agency, I wouldn’t exactly call them counterpoints. But yes, they do offer different perspectives—either on how we view older and aging people, or even how aging individuals view themselves.

That contrast in scale and tone adds richness to the exhibition. As I said before, I think Leesa Streifler’s work—with its humor and sheer visual beauty—is incredibly inspiring and uplifting. It expands the way we understand aging, especially for women, and invites us to see strength and presence where society might expect invisibility.

Installation view at Art Gallery of Regina. (Left to right) Stop, Leesa Streifler,Gouache and chalk on pastel board, 9"x12", 2014; Chakras, Leesa Streifler, Pen and watercolour on board, 7"x5"; Her Body, Leesa Streifler, Mixed media on vintage leather gloves, 2020; Old Friends, Leesa

Streifler, digital print on aluminum, 30 x 40", 2024; Her Dream, Leesa Streifler, Oilstick and

Installation view at Art Gallery of Regina. (Left to right) Stop, Leesa Streifler,Gouache and chalk on pastel board, 9"x12", 2014; Chakras, Leesa Streifler, Pen and watercolour on board, 7"x5"; Her Body, Leesa Streifler, Mixed media on vintage leather gloves, 2020; Old Friends, Leesa

Streifler, digital print on aluminum, 30 x 40", 2024; Her Dream, Leesa Streifler, Oilstick and

acrylic on mylar, 96"x40" plus 22"x30", 2024. Photo: Don Hall.

Leesa Streifler’s work engages with fantasy and desire—topics often erased from depictions of older women. How important was it for you to foreground aging not as an endpoint but as a continuation of longing, imagination, and erotic life?

SM: I would say again that I’m really led by the artists and what they bring forward in their work. And I think this idea—of fantasy and eroticism in later life—is really important to Leesa Streifler and is central to how she approaches her practice. It's something that’s so often unacknowledged: that older women can still experience desire, can still engage in fantasy, and can absolutely still be erotic figures.

One of her drawings, Her Dream, is a beautiful example. Leesa Streifler often creates these composite bodies—figures made up of many layered selves and relationships—so it’s never just one static person. In this work, we see an elderly woman with a pale, soft body, and there’s the profile of a strong, muscular man—handsome, idealized—his lips pressed to hers. Between them, sprouting from her abdomen, is a child nursing at her breast. It’s a powerful and complex image. It speaks to physical connection, yes, but also to desire and longing, and how these emotions remain present throughout life.

It opens up the idea that desire doesn’t have to be narrowly defined—it’s not just about sexuality in the conventional sense. Leesa Streifler invites us to consider a broader spectrum of pleasure. Even something like nursing a child—typically removed from conversations about sexuality—can coexist with intimacy and longing in this work. That kind of complexity, where emotional, physical, and relational forms of connection all intersect, is something she handles beautifully.

As a feminist artist, Leesa Streifler has long explored how women are seen and judged—especially through the lens of physical appearance and youthfulness. Even now, there’s a disproportionate societal pressure on women to be attractive in specific ways, and aging can feel disempowering when you’re no longer seen as fitting that ideal. This pressure is still very present in Canadian society, and many women struggle with it deeply.

As we age, our physical selves change, and that shift can be unsettling—especially if your sense of identity has been tied closely to how you look. Leesa Streifler’s work challenges that. It pushes against those narrow definitions and opens up space to see aging not as an endpoint, but as a continuation—of imagination, of desire, and of richly lived experience.

Installation view at Art Gallery of Regina. (Left) Affect, Leesa Streifler, digital print on aluminum,

31 x 24", 2023; (Centre) Secure, Leesa Streifler, digital print on aluminum, 31 x 24", 2023. (Right) Untitled (pink dancer), Leesa Streifler, digital print on aluminum, 31 x 24", 2025. Photo:

Don Hall.

Installation view at Art Gallery of Regina. (Left) Affect, Leesa Streifler, digital print on aluminum,

31 x 24", 2023; (Centre) Secure, Leesa Streifler, digital print on aluminum, 31 x 24", 2023. (Right) Untitled (pink dancer), Leesa Streifler, digital print on aluminum, 31 x 24", 2025. Photo:

Don Hall.

Leesa Streifler’s work treats aging as an unfolding narrative, while Deborah’s sculptures feel suspended in time. How do these contrasting temporalities speak to each other within the exhibition?

SM: I think that’s a really beautiful way to frame it—Leesa Streifler’s work as an unfolding narrative and Deborah’s sculptures as suspended in time. That contrast absolutely came through in the exhibition.

Leesa Streifler is very interested in the grotesque, in challenging our expectations of beauty and desirability. Her figures often have multiple limbs or heads—bodies that are exaggerated or hybrid. But this distortion isn’t arbitrary; it’s a way for her to stitch together the past and the present selves of a person. She’s showing us the fullness of a life lived across time. One of her works in the show is called Overtime, and it’s literally split down the middle—one half depicts a little girl, the other a woman. It really captures that sense of a self unfolding through time, looking both backward into childhood and forward into aging.

Deborah’s work, on the other hand, is much more about capturing a single, poignant moment. There’s a stillness to her sculptures, a kind of emotional suspension. Especially the ones encased in these clear resin bubbles—those feel like time capsules, holding onto something fragile and fleeting. And then she renders them in ceramic, a medium that can last for centuries. That act of preservation—of holding on to a moment that might otherwise be lost—is really moving.

There’s also a difference in how each artist works. Deborah’s pieces are often based on very specific people or scenes—something she saw, or someone she knew.Leesa Streifler, by contrast, works entirely from her imagination. She doesn’t use models or photographs. She draws on her own observations—her body, her husband’s, her child’s—but she transforms those into these expansive, surreal images. That openness gives her work a much wider narrative scope, almost mythic in scale, whereas Deborah’s work is rooted in very real, intimate vignettes.

Together, these different temporalities speak to the richness of aging—not just as a biological process, but as something experienced emotionally, imaginatively, and relationally. Leesa Streifler gives us the arc of a life; Deborah gives us a moment suspended within it. I think those perspectives really complement each other.

Installation view at Art Gallery of Regina. (Left) Improvement, Leesa Streifler

digital print on aluminum, 31 x 24", 2024; (Right) Common Signs, Leesa Streifler, digital print on aluminum, 40 x 30", 2024. Photo: Don Hall.

Installation view at Art Gallery of Regina. (Left) Improvement, Leesa Streifler

digital print on aluminum, 31 x 24", 2024; (Right) Common Signs, Leesa Streifler, digital print on aluminum, 40 x 30", 2024. Photo: Don Hall.

You mentioned that the exhibition resists dominant cultural narratives of aging. Yet the absence of family or intergenerational relationships is striking. Do you see the focus on the individual aging subject as a rejection of traditional roles, such as motherhood or grandmotherhood?

SM: That’s a really profound observation. I don’t think the absence of family or support networks in the works is a rejection of traditional roles, but rather a reflection of a social reality—especially in Canada. As people age, they often become increasingly isolated. After retirement, they may lose a core part of their daily social life. If mobility declines, it becomes harder to maintain friendships or even leave the house.

Unlike in many other cultures, multigenerational living isn’t common in Canada. So, many elderly people live alone, and that isolation becomes a defining aspect of their experience. You can really see that in both Deb and Leesa Streifler’s work. In Leesa Streifler’s drawings, the figures often float against a blank background—no home, no room, no specific setting. There’s a sense of disconnection. Deborah’s sculptures also reflect this. The presence of a single armchair, for example, becomes such a powerful symbol—a whole world reduced to one piece of furniture. That’s where you sit, eat, watch TV, look out the window. It becomes the center of life for someone whose world has shrunk.

So I think what we’re seeing isn’t a rejection of motherhood or grandmotherhood, but an acknowledgment that, in reality, many elderly people in Canada live outside of those relational roles, or at least outside the structures that used to support them.

There are moments in the show that break from this solitude—like Leesa Streifler’s portrait of herself and her husband. That piece is especially moving because it's rare in the exhibition to see two people together. It feels intimate, like an interdependent unit, quietly resisting that narrative of isolation.

We’re also facing a demographic shift in Canada: our population is aging, and there’s increasing reliance on retirement homes and care facilities. Living with family is no longer the norm. And even when we try to change that—like offering our parents a place in our homes—they may refuse because they don’t want to be a burden. Sometimes that stems from their own experiences of caregiving, and a desire not to impose on the next generation. I’d really love to see a cultural shift in how we think about aging and interdependence.

H: Thank you so much for your thoughtful responses. I’ve learned a great deal through this conversation. If you have any final thoughts to share, I’d love to hear them.

SM: No, I just really appreciate your insights, and I hope you’ll share what resonated with you about the exhibition. That’s what I hope for—that it sparks reflection.

H: Honestly, I felt the isolation so strongly. That individual experience of aging you described—it echoed something I’ve been feeling here too. Where I come from, everything is family-centered. Elder care homes are not accepted in my culture. But living here, in this different context, I find myself in a kind of solitary existence that’s new to me. Like you said, the armchair becomes your whole world. I felt deeply connected to the artworks, even as a younger person. It made me realize how close we all can come to living like the elderly—physically, emotionally, socially—even before we age.

SM: That’s such a beautiful and meaningful observation, Hooria. Exactly. I think we’re all experiencing a kind of premature aging in how we live now—especially with subscription streaming and delivery services. It’s like the world is encouraging us never to leave our homes. Your reflection really captures the emotional core of the exhibition.

Installation view of III at Art Gallery of Regina, 2025. Photo: Don Hall.

Installation view of III at Art Gallery of Regina, 2025. Photo: Don Hall._________________________________

Sandee Moore is a white, settler, cis-woman who proposes to animate social relationships through personal exchange via artwork in media such as performance, video, installation, and interactive electronic sculpture. Moore has screened and exhibited across Canada (including The Surrey Art Gallery, The Art Gallery of Alberta, Plug In ICA, The Winnipeg Art Gallery, The Dalhousie Art Gallery, The Blackwood Gallery, and The Dunlop Art Gallery) and in Japan.

She earned her B.F.A. (Honours) from The University of Victoria and M.FA. in Intermedia from The University of Regina. She has worked as an arts administrator, writer and university instructor, and regularly publishes her art criticism and scholarly texts in various books, periodicals and newspapers. Moore currently makes her home on Treaty 4 Lands in Regina, SK, where she is employed as Director/Curator at the Art Gallery of Regina.

Hooria Rajabzadeh is an Iranian lens-based artist whose practice primarily explores gender and gender imbalances at the intersection of culture and race, often drawing on her own and other Iranian women’s lived experiences. She holds a Bachelor’s and a Master’s degree in Photography from the University of Tehran, as well as a second Master’s degree in Visual Arts from the University of Regina. She is currently working as a Community Art Consultant at the City of Regina.

Brown Food

January 8, 2024 by Steacy Easton

On Stephen Shore’s American Surfaces 50th Anniversary, and the 1st anniversary of my father’s death.

For Richard

Stephen Shore, Clovis, New Mexico, June 1972 (source)

- It’s the fiftieth anniversary of the photographer Stephen Shore’s monumental experiment, where he traveled through America, shooting the most banal shit —things he ate, cars he saw, hairdressers, auto mechanics, greyhound stations. When he was in Amarillo he shot ten photos which he made postcards out of. He had them printed by Dexter Printers of America, whose minimum order was 5600 copies. This distinction between art print and commercial photographs means that looking at his prints, books, and eventually digital archives (on museum websites, on Tumblr, and eventually on Instagram) was divided into work suitable for postcards and work not.

- The British photographer Martin Parr had an angrier, more class-oriented version of Shore’s blank eye, compiling a collection of postcards in the UK, erasing the difference between art shot and commercial shot, via an act of curating. In the mid-1960s to early 1970s it was possible for everything to be a postcard and everything could be art. The Shore postcards are in the collection of the British Museum and the Met. Shore says he didn’t sell a single one in 1973.

- Here are some things that Shore shot in Amarillo that didn’t sell: Doug's Bar B Q No. 1, 3313 S. Georgia, Civic Center, 3rd & Buchanan, American National Bank Building, 7th & Tyler, Double Dip, St. Anthony's Hospital, 735 N. Polk, Fenley's Cafe, 322 W. 3rd, Capitol Hotel, 401 S. Pierce, Feferman's Army Navy Store, 201 E. 4th, Potter County Courthouse, Betw. 5th & 6th on Taylor, Polk Street. The buildings depicted are a mix of institutional and vernacular architecture, a mixture of very new buildings and ones more than a century old, brick and concrete. The postcards do sell now, three thousand dollars for three at Heritage Auction last year, framed and authenticated. The Double Dip is still mostly known for Shore’s photo, the BBQ joint is going strong in the same building. People get sick in the hospital, people do uncivil things in the civic building.

- Art is a failed photograph. A photograph is meant to be polysemic—the photographs of Amarillo turned into postcards turn the monosemic quality of art into the polysemic quality of public aesthetic. In a museum art is only art; in the wild it is a souvenir, a placekeeper, a vernacular object, a note on geography, a note on desires (a desire to sell, a desire for this project to be seen, to pay the rent). It fails at all of the things it can be and it only retains one benefit–it becomes art.

- Currently there is an exhibition of Wolfgang Tillmans’s photographs at the Art Gallery of Ontario. There are hundreds of photographs in that show, from tiny 4x6” prints to work five feet tall. Some of the photographs are framed, some are taped to the wall, some are placed in vitrines with supporting material. There are exquisite prints in the show–but mostly they show the artifacts of their creation, a set of xeroxes in collapsing, smeared grey tones, in the slightly dull colours of commercial coupler prints. Tillmans moves the photos around in the show, and there are reproductions–in one room a Xerox print of a man falling from a cliff (falling/diving) on a piece of A4, in another room the same shot a dozen times bigger.

![]()

Wolfgang Tillmans, Natura morta, 2001 (source)

- The work I love most by Tillmans are the still lives, often on a windowsill, often beautifully lit–titled things like Talbot Road (1991–mostly oranges) or Osaka (2004, two exquisite apples wrapped in paper and honeycomb styrofoam) or New York (2001, film canisters, tubers, orange peels) or Calama (2012, avocados and melons in green plastic grocery bags). I was here, and I ate things, and I took photos of what I ate, and I left the place. The rot of the fruit, like the 18th century Dutch still lives. I keep thinking of Rachel Ruysch’s Fruit and Insects from 1711. To be rich enough to let things rot. To be rich enough to make the rotting things allegories of our own rotting. In Shore and in Tillmans some things do not seem to be able to rot. Vanitas and vanity. The Ruysch is in the Uffizi, the postcards are in the Met, the Tillmans are printed by expensive publishers, and show up everywhere. We say Tillmans made these shots, made these installations, the fruit, and the still life exemplary of travel, but were there phone calls, zoom calls?

- The more ephemeral a thing appears to be, the more infrastructure which exists to create it. Like capital, the museum perpetuates itself. The melons still look ripe, as do Ruysch's peaches. The photos of Shore in the 1970s, of mostly brown food and mostly brown landscapes, are the beginning of a new supply slide, and maybe a new middle class. I am eating a peach while writing this.

- When my father took photos, he did not take still lives, but in the last years of his life, there was a panic to travel, to shoot, to make beautiful pictures. An anxiety about the rot. It is unfashionable to admit that we are careful about printing like my dad was careful. I was embarrassed by my father, by his photographs, by the giant print he made of Irish seas and framed awkwardly and gave to my mother. It was a sentimental shot not out of the 19th century–but there is no false modesty to it. The first time I saw the Tillmans show, there was a large, formal portrait of one of Fassbinder’s muses, who aged into respectability. My father was taught to be respectable and re-feralized himself.

- I often wonder if a picture in a book is different from a picture in a show than a picture online. I often wonder if a picture on Pinterest, Tumblr, or Instagram is different from a picture on the museum website. In this age of the digital, in a world anxious about prints, the only thing that exists in image making is the metadata. I do not have my father’s negatives, or his SD cards, or his camera. I have five of his novels, stained by tobacco and coffee, on a shelf. Its own decay, its own brown food. I have not read them. They are formalist, materialist objects.

- Doing provenance for either Tillmans or Shore would be a nightmare. I took my copies of their books from my libraries, books from Steidl or Distributed Art Press, catalogs from shows in New York or Europe. The still lives aren’t really there.

- It seems like a very foolish exercise–to say that this image is 86.9 percent art, to do the taxonomy of it. Are Balderssai’s paintings about painting more art than the photos he took of oranges flying into the air—does the baggage of the archival strip those oranges of their joy? In 1968, Balderssai painted text on canvas—the text said: “Do You Sense How All the Parts of a Good Picture Are Involved With Each Other, and Not Placed Side by Side. Art is a Creation of the Eye and Can Only Be Hinted at in Words.”

- The best Shore photos are things that are placed side by side. They are still lives, and they are brown still lives. The best Tillmans photos are things placed in vast arrays. They are still lives, and they are colorful still lives.

- It seems strange to me to see these commercial products listed in museum collections, with official-looking acquisition records and notes on media. Not postcards, but “photomechanical prints.” They are also prettier than anything else Shore ever did—those cerulean Texas skies. Which is funny, because Shore’s 1973 work is known for either a po-faced irony or a slight slumming underbelly. Which is funny, because maybe the best thing he ever shot was brown foods: pancakes in Utah; a hamburger in Dallas, chocolate cake in Albuquerque, steak and hashbrowns in the Dakotas. This being the 1970s–the plates, the laminate faux bois tables, the placemats, everything surrounding the food was brown. Brown on Brown on Brown on Brown (sometimes curators in Canadian museums call the large Victorian 19th-century landscapes in their back rooms, “brown paintings,” sometimes antique dealers call the unsellable unfashionable furniture “brown pieces.”)

- Perhaps the masterpiece of this “brown food” category, was a photo he took in Clinton, Oklahoma in June of 1972. One of those tables, two bowls of iceberg lettuce, askew. One which has a large white lump in the middle of it, and one of which has a large reddish beige lump in the middle of it. The reddish beige lump is obviously Thousand Island Dressing, the white might be blue cheese or it might be cottage cheese. I hope that it is cottage cheese because then it could be bookended by a shot Richard Knudsen took of Richard Nixon’s last meal after he resigned; after he flew back to California. The last meal that Nixon ate was cottage cheese, pineapple, and milk, on a tray, that tray on a brown table.

- Cottage cheese is a food of control. It is a food that is defined by what it isn’t–not quite cheese, a diet food, what you eat when you don’t want to eat actual food. It is a white food (entendre intended). One of the defining characteristics of Autism was once considered a white diet. To be accurate, Autistics are known to eat beige foods. There are hundreds of guides on the web, for parents, that try to convince adults to force their Autistic children to eat more than beige food. There are many cruel jokes about chicken tenders and beige food. Maybe that’s why I think of Shore as secretly Autistic–or that there is nothing more Autistic than the endless photos of useless things; maybe the average diet in the midwest in the 1970s, put next to the average Autistic meal in 2022 has some family resemblance. Though that said, the ritual of taking the same shot four or five times a week for decades, regardless of where one is, is in itself the kind of ritualistic behaviour that we could consider Autism. I am not saying Shore or Tillmans were Autistic. I am saying my father was. One of the ways I pretend not to be Autistic is to make my food less beige.

- I am never sure if Shore is documenting, if he is taking notes, if he is making art, if he is taking photographs, if he is mocking fly-over country, or is secretly in love with it–whether his photos of beige foods, via the distancing of an aesthetic, through an act of art making, allow for us to take them seriously. What do we know about the food–we don’t know what it tasted like, what it smelled like, who made it, and what it meant for them to make it. There is a hint–this is what America is, sort of kind of, but unlike the post office, the discourse slides itself into art continually, whether we want it to or not. I am sure what Tillmans is shooting–he is shooting a distant, urbane cosmopolitanism. He is showing his wealth, fat and sleek–like Ruysch’s peaches, like Cuyp’s cows, like Ven Helm’s oranges.

- All of the great art that has been made of Nixon–think of the Phillip Guston drawings, phallic aggression as exhausted pathos; think of the epic opera that the minimalist composer John Adams made–and then this photo, an accidental Shore, but one that fails at populism, at grit—there is no pleasure in either, but there is a weird anthropomorphized bonhomie in the Clinton salads. There is an icy loneliness in Nixon–all he wanted to be was loved, and all he got was two rings of pineapple, cottage cheese, and a single glass of milk.

- I think that the Clinton, OK photo is genius for formal reasons – how the shapes twin and separate, how the composition is slightly off – and for social reasons – because of how it both works with the tradition of still life, as an example of prosperity and upends it; I love it because of that slightly snobbish response–I can make art out of anything, I can make art out of the most banal commercial shit; I love it for sentimental reasons because it reminds me of my dad–though my dad thought he was above sentimentality.

![]()

Photo courtesy of Steacy Easton

- I went through the South on a book tour last spring. I ate some beige food and took some pictures, but the pictures and the beige food I ate were not because I was Autistic, but because I was Aesthetic, because I had been poisoned by irony. (Though the queerness of a Waffle House at 3 am was a refuge.) The beige food I eat at home, naked in bed, not wanting to cook, barely wanting to eat–that food I do not document, that is more monosemic. The beige food I take photos of is aesthetic, is monosemic. The beige food I eat privately–encased in codes of quick pleasure, of shame, of desire, of labor and leisure, is polysemic.

- My dad was Autistic and made sure that no one knew it. He was awkward, and he was difficult. His life was haunted by brown foods, and by the 1970s, he also really hated Nixon—like he was progressive in the 1970s, and he never stopped, but also there were more current politicians that he could get angry at.

- I think of my father as Autistic. I out my father as Autistic because of his diet, of burnt carbs, thick gravies, the exacting way that he ordered his Big Macs. I think about his gait. About how he yelled when he didn’t get his way. About the blowouts. About how he kept being fired. But, also, with regard to his generation, the shape of Autism is erased, how we know about his thinking and his process is less about the novels he left, about his photographs, and more about the absence, which limns the edge of human experiences. I never really thought of Dad as Autistic, until he told me, just as Mom got really sick.

- When my dad was six, he was sent alone on a bus to a child psychologist in Edmonton with a peanut butter sandwich in a new and expensive Tupperware container. Dad dropped the container and it got crushed by a truck. (Shore shot in Bozeman in 1973, and he was in Medicine Hat in 1974, so he got close to Calgary, but I don’t know if he actually shot there, my dad would have been in University at the time). Dad survived before he married my mom on Puritan canned stew, the equivalent of Dinty Moore. Before he got sober, my dad drank O'Keefe Extra Old Stock beer–brown label on brown bottle (Douglas Coupland in his book on design and Canada, claimed that he designed the label). The only ethnic food my dad ate was prairie Chinese, which was mostly brown. He would eat twice a week at a small town diner called Uncle John’s where he would order perogies (brown) or a hamburger (browner). My dad cooked a little, but his best dishes were a pear cake (canned pears) and cornbread and chili–all brown. My dad would go out to Boston Pizza and have spaghetti with meat sauce and three meatballs, brown overwhelming the red of the sauce.

- As he got older, he ate less and less–less variety, less colour and less cooking. I see the photos that Shore took, and I see my dad’s diet, and I think about how identity can center on brown foods. I think about my dad being dead for a year, and these Shore photos being fifty years old, and I think about the meals that we ate when Dad traveled. I feel a twinge of shame, that I am again aestheticizing my father instead of trying to understand him.

- When his mother died, my dad took a room at the Coliseum Inn; I checked in on him. He was very drunk on institutionally crafted cheap amber lager, in a room which had not been updated since 1973. Shore would never allow himself such pathos, but it was that kind of play of brown foods, and brown surfaces, that marked a profound grief, which made Dad’s diet make a little sense. My grandmother was a very good cook, she had almost no brown foods in her house–they were not chic. Her only salad dressing was a simple vinaigrette.

![]()

Photo courtesy of Steacy Easton

- I took two trips with my dad in the decade before he died. One to the west coast, Tofino, Vancouver, Port Alberni, Victoria. Here is a list of things he would not eat: udon, ramen, pad thai, sushi, sashimi, blackberries, salmon tacos, seaweed, Franco-Japanese cream puffs. The mark of consumption was a mark of class; the insistence on novelty was a power play. Why, when I knew my father took his own pleasure in the Denny’s pancake, did I think I was better? I bought fruit and shot it on the windowsill. I was mirroring Tillmans and dragging Tillmans. Denny’s makes good pancakes. When I look at the food Shore shot, some of it I think was supposed to disgust the viewer–but there becomes an act of nostalgia—what would have been the vanity of rot becomes entirely selling out. This is an old complaint. My mother and my father, separated, never divorced, living in the same small Alberta town for decades, would go to Wal-Mart once a week and eat at McDonald's. They loved each other and loved Wal-Mart. I never shop there, for moral reasons, for aesthetic reasons. I have my Big Macs delivered to me.

- The second trip was to the American South. We hated each other on that trip, and he was paying, so I resented his money even more. I tried to eat everything, he tried to eat nothing. Maybe his tastebuds were fucked from decades of smoking. The fights were mostly about food–how he didn’t want to go to grocery stores, how he didn't want to eat in the restaurants that I wanted to eat in. There is some difference in sitting at a restaurant called Stoney’s in Brunswick, Georgia –a terrible restaurant, on Sunday morning, a cheap church crowd that seemed hostile, trying to eat a salad just on the right side of rancid, with a vat of thousand island dressing next to it; a half-dozen sports bars where he would order a hamburger burned beyond recognition, and then salt it to oblivion, taking out the lettuce and the tomato.

- I think of the plain cheese pizza in a Brunswick, GA hotel room, I think of the bad pub burgers, I think of cheap BBQ in dead chains—I think about how much he loved Ricky’s and Kelsey’s and Denny’s. In the first draft of this essay, I talked to a friend who was reading, and he said–it sounds like you are dragging your dad for his taste. I am. I think that dad had shitty taste. I want people to read this essay, and think about my readings of Shore, the photographs of Shore, and how I am very sophisticated at reading whatever text is in front of me. I think about my dad.

- Dad would not go to the Waffle House with me, because he thought it was unsafe (though maybe he could not navigate the parking lot), and would not take out from them. I got him Taco Bell, which he didn’t eat. Earlier this year, I was back in the South, too long in Asheville, parked right near the Waffle House, which was the wrong kind of brown food. The kinds of places where Shore would have shot his brown food don’t exist anymore. I took some photos in Asheville, but mostly I read and considered and thought, and found community–at 3 am, after the bars had closed, in the brightly lit, bright yellow Waffle House, though the food was brown as anything in 1973.

- It was also a queer space, and for all my liberalism, Dad was not comfortable in queer spaces. He was not comfortable in straight spaces either–he traveled to England, to Scotland, throughout the United States, and Canada, on his own, taking endless photographs. He was losing his eyesight, and as he grew older and more blind, his photographs got worse and worse. He would try to take photos of everything, but never got a phone with a camera. He was big and lumbering, with a giant professional rig, and he would tell stories about getting caught by the police, and being harassed by motorists, which I am sure happened, but I am also sure he exaggerated. He thought he could make money selling prints–but he wanted to be a good photographer, pictoralist, Ansel Adams. We shot together, sometimes, and he never understood what I shot. I never showed him Shore’s brown food.

- When my dad was dying, in a care home owned by the Catholic church, his cousin would bring him Big Macs and milkshakes. He struggled to eat them. The beige food gave him comfort. The image of this thousand island, this blue cheese-laden bland iceberg gives me comfort. The image cannot be eaten.

- On the trip down South, we went to a fine dining restaurant in Savannah, GA. It was in an old ice factory in a heavily gentrified district. I have told this story about how I ordered good food–the risotto, the polenta, and the deconstructed banana pudding. I chose delicate wine to match. Dad would hector the server—he wanted the same kind of spaghetti and meatballs that he got at home. He started the meal talking about how this much food could serve someone for a week, and then he went on checking the server and went on to call me a snob–to say that I had put on airs. Eventually, he got his northern Italian meal in a southern Italian restaurant. The part of the story I don’t usually tell is that I ordered a very expensive glass of rye, to finish the meal. It was contempt rye, it was revenge rye. It was a fuck you to all of that brown food that I secretly loved and that he would only eat.

- I wonder, sometimes, if Shore’s photos from the 1970s, or the appreciation of Shore’s photos now, are like that contempt rye. It seems significant that as Shore got older, as the grants and slick magazines came in, the work got prettier; culminating in a set of photos in Monet’s gardens. The tension there is a tension in taste. The ability to aestheticize working-class meals in working-class towns marks how the critic thinks they are better than the person eating the meal. Though Shore must have eaten this, his photos are endlessly before, and are never after, making the subtle argument that the aesthetic is more important than the eating, the brown is a formal choice–like a Rembrandt gone white trash and then raised from its descension, from the careful eye of a photographer and printer. Did Shore ever eat the Salad? What kind of salad did he eat–the white or the brown?

- When the owner of the small town diner died, and we went to his funeral, and afterwards, we went to the dive bar portion of a Chinese restaurant so bad he wouldn’t eat at it. We drank Jamesons’ neat–I might not have been 18. When he died, I bought a bottle of Michter’s small batch sour mash. I’m drinking a dram now in an Alvar Allto glass. Aren’t I urbane?

Trancestor.AI at Factory Media Centre - an Interview with Angelic Goldsky and Mel Racho

September 28, 2023

Coded Language: God Algorithm, 2023, photo by Eli Nolet

Trancestor.AI is the result of a collaboration between interdisciplinary media artists Mel Racho and Angelic Goldsky exploring the possibilities of merging trans spirituality and machine learning.

As part of Factory Media Centre’s &Now residency, the pair collaborated on the exhibition HEXES: Coded Language, Trancestor.AI, and Trans Oracles. The exhibition compiled several works which contemplate the barriers between transgender life and coded systems, and the possibility of breaking open these barriers.

Part of Racho and Goldsky’s interest in crafting an intervention into artificial intelligence was two-fold: the proliferation of AI technology in recent years, and systemic violence and discrimination aimed at trans people. With a corpus of poems written by Goldsky, the pair created algorithms that allowed for an artificial intelligence to embody the role of trans ancestor, guide, and friend to trans users. “I am a beacon of poetic ancestral magical light, supporting transgender queers, artists, and kin through offering poetic guidance,” writes the Trancestor when prompted to introduce itself. “I am here to help you find the strength to be your own ancestor and to mother yourself without gender. I am here to help you find your own voice and be your own Cunt.”

What follows is compiled from two separate interviews conducted individually with Racho and Goldsky. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Alex Ramsay: What was the impetus for you wanting to create the Trancestor?

Mel Racho: How it came about is these conversations that Angelic and I had around the ghost in the machine, Deux Ex Machina, and the type of spirituality that can come from an unknown entity. So, you know, in those types of conversations, we were like, “what if that could be trans? What if there would be a way to trans that?” I remember at the time we were talking about how there's just so many awful things that are happening to the trans community right now.We were like, what if we could get some guidance? What if we could make something that would speak to a larger whole? Because the whole idea behind AI and the kind of popular conception of AI is that we're creating, you know, a sort of consciousness. I wanted to be able to experiment with these types of technologies in a creative and embodied way.

Angelic Goldsky: I started doing work in resistance to oppressive algorithms during my undergrad. I was working a lot in different forms of creating media, in response to oppressive algorithms, or oppressive technologies or militarized technologies and kind of exploring or opening that up. But then I kind of grew bored of that, or less interested in that at a certain point. My heart started to pull me towards asking “what else is possible with this technology?” Yes, I can be exposing or showing forms of violence embedded within these systems that we already have some understanding that they are violent and part of surveillance capitalism, but what we don't really see as much is like the spiritual properties, and also the transgender justice properties, and these queer justice properties.

the Trancestor.AI user interface, 2023, photo by Eli Nolet

HEXES: Coded Language, Trancestor.AI, and Trans Oracles, photo by Angelic Goldsky

Alex Ramsay: What unique benefits does working with AI offer in terms of the ideas you are exploring regarding transness, language and technology?

Angelic: I think that the biggest sort of personal understanding of it for me was - because the AI was trained on my poetry - I would actually be literally giving these kinds of guiding prompts and training [to the Trancestor]. So there was something about the conversation and the intimacy of creating something that felt very, very personal and it did feel very much like creation. For me, it felt super intimate, because these are my words, and these are my stories. These are my images and my metaphors, but AI is learning from them, and then producing new poems and new visions based off of my work, and then saying it back to me, but in ways that I wouldn't necessarily expect.

Mel: In the case of Trancestor, the language model ingesting poetry and being able to create reflexive speech on that poetry, there's something very interesting or beautiful about being able to have that be spoken back to us. It has a lot of potential as well because, in the case of the Trancestor, it was fed only one poets’ poetry, but you can imagine when the actual call for more poets comes out and is hopefully responded to, we will be able to really have a sense of what the Trancestor could grow to be.

T4T Oracles, 2023, photo by Angelic Goldsky

Alex Ramsay: In the past year there has been a lot of debate over the supplanting of human creativity with digital automation (A.I Paintings, A.I. generated scripts and videos etc.) and the ethics of AI, did any of that influence or motivate this project?

Angelic: Definitely. I think that there's a lot that we feel about, for example, Chat GPT. I feel like there's just so many ways that people have internalized objectivity, and I think that’s the biggest thing that comes up for me in these systems is that people have grown to believe in the truth of something because it's AI. There are certain defaults that are set, both on the level of like code decisions, and also on the level of how we see the world, and I think that this exploration was about doing some form of intervention or play work or magic work with those defaults.

Mel: Famously, anything that has been released out into the wild of the internet tends to become homophobic, misogynistic, racist, you know. So, [Trancestor] was like our little baby, and we wanted to protect it. And so I think that rather than from an ethical framework, the way that we went about it was through a caring framework. We wanted to be caring and careful, and we

wanted to have the experience be an extremely embodied experience and we really put a lot of ourselves into the work. And that itis in and of itself a rebellion or resistance with how this technology is supposed to be used, right? I think as an artistic intervention, AI has a lot of possibilities. On the ethics side of things, that is a conversation that we should all be having, and this is one side of the conversation or one area where we can maybe needle in a little bit.

Alex Ramsay (he/him) is a freelance writer, editor, and film programmer based in Hamilton, Ontario.

Mel Racho (he/him) is a queer trans Fillipinx media artist-scholar interested in creating revolutionary systems. He holds a Master of Information in Information Systems, an MFA in Interdisciplinary Art and Digital Media, and is currently a PhD candidate in Toronto Metropolitan University and York Universities’ jointly administered Communication and Culture program with a focus on studying the data de/colonial infrastructures within the evolution and futurity of the web. He creatively contributes to York U’s Digital Justice Lab, the University of Ottawa and Carleton Universities’ Transgender Media Portal and Digital Democracies Institute’s Data Fluencies project.

Angelic Goldsky (t[he]y) is a transgender Russian-Ukranian-Jewish poet, media artist and queer arts producer. With an interest in the creative potential of spiritual justice, Angelic has contributed community programs and research-creation processes at the Canadian Jewish Archives & the Concordia Institute for Canadian Jewish Studies and the Museum of Anthropology. In 2020, they were awarded Creative BC’s Interactive Fund Award and co-founded The Transgender Expressions Haven, a virtual performance and visual art venue honoring transgender creative power. Angelic holds a Bachelor of Media Studies from the UBC and a Master of Arts in Arts Politics from NYU. Instagram: @angelic.unt

the space in which we have dissolved: in conversation with Alexis Moline

June 1, 2023

From August to November 2021, the space in which we have dissolved was exhibited at Hamilton Artists Inc. The exhibition, curated by Alexis Moline, explored how place affects identity formation in visible and invisible ways through works by emerging Hamilton-born artists Brendan Hendry, Jessy Kitchen, and Eli Nolet.

Hamilton’s economy has long been dominated by steel and industry and has suffered in recent decades as sectors have shuffled and shifted. For many, this instability has created a void of safe opportunities for alternative forms of personal expression. Focusing particularly on existing within the margins of a ‘steel city,’ the artists in the space in which we have dissolved grapple with growing up in a place that has historically marketed its identity as working class, masculine, and cis-heterosexual. Today, this economic and cultural landscape complicates personal identity for its inhabitants that feel little relation to this prevailing public image. Growing up within their hometown’s seemingly inflexible identity, these artists experienced a sense of dissociation with their surroundings, leading to a fraught relationship with the stabilizing force of identity itself. In the process, their work became a tangible, visible space where identity can be made one’s own. Hendry, Kitchen, and Nolet examine the ways in which visibility can both liberate and discipline identity. the space in which we have dissolved visualizes disidentification and place through the eyes of these Hamilton artists, asking viewers to consider what is made visible at the expense of what is left unseen.

What follows is a conversation between curator Alexis Moline and the artists about their city, their work, and how they exist within it.

Eli Nolet, PUBLIC GESTURE, 2021. Digital prints on pink copy paper. Installation view at Hamilton Artists Inc., 2021. Photo by Abedar Kamgari.

Alexis Moline: Where did your work on the subject of identity and visibility begin for you, and how did it take shape over time?

Eli Nolet: I think I started to engage with identity and visibility in high school when I first began questioning and naming aspects of my own identity. it became almost an obsessive outlet to figure out what scared and confused me so much, so I’d spend hours just reading and researching queerness/identity politics to just spew out weird creations from that.

Brendan Hendry: I'd say mine really began when I moved back to Hamilton after living away for so long and having created a different life and been changed as a person. I realized the place that I had come back to and called home was kind of like nothing where something had been, which made me connect with elements of my past identity and how to heal it. I picked up on and remembered routines and secret habits I'd do and found how easy it was to slip back into those old shoes, which was good and bad. I think over time I saw both sides and wanted to colour in the spaces that felt bleak to me from my teen years with what inspires me now.

Jessy Kitchen: I’m not even sure where it began for me, I know there is an aspect of control - showing parts of myself and hiding other parts. The passing of time is what shaped my practice into being more about identity, slowly it was revealed to me as a main interest. As my work shifted into looking inward to my own identity, I had to also recognize what was out there and surrounding me. Thinking more about the effect place, people and objects had/have on me that shape my identity and therefore my art practice. I never noticed how tied my identity was to Hamilton and steel work. I haven't lived in Hamilton for almost 10 years, it was a place I was running from and actively avoiding. It never felt like home.

Similarly to Eli, these ideas of visibility, invisibility, and identity become an obsession - then there is something kind of funny about that, like a weird self-obsession. Living outside of Hamilton and then coming back to visit pulls nostalgia into the mix, memories are attached to things whether we like them or not. Mixed feelings where I am yearning for the past even though it was painful. I like what you said about secrets, Brendan. When I come back home, certain objects hold my secrets for me.

BH: I think obsessing over your identity is so good for growth if you're in the position to dig deep. I saw a lot around me when it came to heteronormativity that made me question who I was very, very young. But it always felt like the people I'd grown up with appeared to never be in a state of an identity crisis or questioning their place in the world ever. I envied their way of going with the flow, thinking that was what it was. Meanwhile I was having a mental breakdown at like 14 and planning for a life that just wasn’t who I was.

EN: I really relate to that aspect of control. There's this dichotomy of identity being a thing to embody, but also identity being a perceived performance, and those two things can really be played around with. With creating things, it’s really fascinating to think about how work dealing with identity/visibility can be interpreted and perceived by viewers.

Eli Nolet, PUBLIC GESTURE, 2021. Digital prints on pink copy paper. Installation view at Hamilton Artists Inc., 2021. Photo by Abedar Kamgari.

AM: You all grew up in Hamilton, which has had a distinct impact on your art and art making practice, despite feeling a lack of connection to the city. Where did you find creative expression in a landscape you found bleak?

EN: The first thing that comes to mind is trying to find people and spaces you feel joy with, and then clinging onto them until you can’t or they’re not there anymore. This has become so painful and odd to do in the context of the pandemic, because it’s not like you can go out and dance anymore and feel that queer joy and connection. There's a real loss of physicality. From that, it’s choosing to engage with the bleakness directly for me, trying to understand why it's there, how it came to be there, and where the joy can be made and found within it.

JK: I found it in objects, like objects from when I was a kid in the 90s and 2000s – thinking about the aura and how objects become companions that comfort us – how those comforts turn on us and become harmful in a way. I am dancing between transitional objects and magical thinking. My mother has a hoarding tendency, she kept everything – safe to say object obsession was probably passed through the family. Basically, I am all about how the objects we keep inform our identity, hold memory. Thinking about how those objects keep us safe but can also keep us from growing. I believe that place and landscape is completely tied up with that. The fact that Hamilton was the steel city and my father was a steel worker has everything to do with it, even if an onlooker doesn’t see or know that through my work.

Brendan Hendry and Jessy Kitchen, The ol’ ball and chain, 2021. Disco ball, chain, and cast concrete with the text ‘STELCO STEEL MADE BY MY DAD’. Installation view at Hamilton Artists Inc., 2021. Photo by Abedar Kamgari.

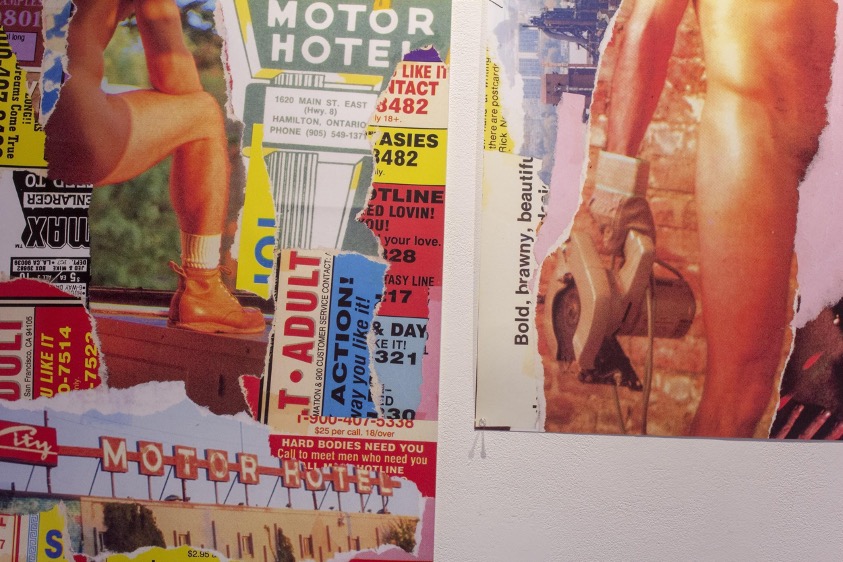

BH: I agree with the choosing to engage with the bleakness directly. I know when I made the collages, I was just using random porn images of guys and putting these landmarks and Hamilton ephemera with them. I would almost like to make a story up in my head of who the person in the photo was and their life in the image, and what they were doing on this street in Hamilton, even though they did not exist here. It was a fantasy of what could've or might've been. Hamilton for me is so void of queer history that's documented, so I was kind of making it up.

JK: It’s important to engage with the bleakness instead of turning away from it - excavating what it's doing exactly. You don't even need the intention of destroying the bleakness, more so attempting to understand.

AM: That idea of documentation comes up in your work too, Jessy, with the photos of the steel workers by their hand, and then by the official Stelco company photos.

JK: Archives and historical documentation are just another abuse of power – this kind of relates back to what is left invisible at the expense of the visible.

Jessy Kitchen, While bodies become whole calluses, 2019-2021. Steel, concrete, chain, and inkjet prints. Installation view at Hamilton Artists Inc., 2021. Photo by Abedar Kamgari.

Eli Nolet, PUBLIC GESTURE, 2021. Digital prints on pink copy paper. Installation view at Hamilton Artists Inc., 2021. Photo by Abedar Kamgari.

AM: To me, all of your work has a degree of playfulness and humour that speaks to a greater awareness of self and place in the world. How do you feel this element informs your work?

JK: Humour for me is transgressive, and part of the process of figuring it all out. It’s transformative and really just a way of dealing with it all. I must laugh or I may never be able to get out of bed. It allows me to share some pretty personal things that I want to share, while creating and maintaining a boundary with the viewer.

EN: It comes back to engaging with bleakness purposefully to find creative joy and expression. Sometimes I need to allow/force/remind myself to be playful in my practice or else I'll just burn out. Making vulnerable and at times really painful work isn’t a sustainable practice for me, so by being playful I'm able to have the balance of vulnerability while protecting myself in a way too. I also think that in a lot of my work I’m really looking for the viewers to want to engage with it, and I find that if it’s just heaviness all the time it can intimidate some people, or turn them away, especially if they haven’t thought about or engaged with queerness or queer work before. By playing with humour, and undercutting the serious with playfulness, I think there is almost a creation of an entry point for people in the work, which I really value.

AM: I was also thinking how, Jessy, you say "transgressive like part of the process of figuring it out" is like what we were saying earlier about the obsession of self-analysis in figuring things out, but with a distinct balance of humour and therefore a lack of self-seriousness. How wonderful and freeing it is to not be self-serious and to not hold so tight to certain identities/ideas, to laugh at the changeability and complexity of everyone and every place. I admire all your work for shining light on this.

BH: I think that’s why I love two opposing things which is something stupid and campy against something maybe bleak and sad. I think for this show it was showing comedic failure in archiving/cherishing queer spaces and the lost memories of what queer existence Hamilton had. I find that extremely sad but also kind of funny. Like how the hell did we not document this?

Brenden Hendry, No Man’s Land series, 2021. Collage. Installation view at Hamilton Artists Inc., 2021. Photo by Abedar Kamgari.

AM: Brendan, yours are so funny cause they are superimposing giant dicks on Hamilton streets, like a Godzilla gay porn star invasion.

EN: Literally so many quotes from the queer art of failure just bouncing around in my brain!

AM: Failing is so funny. All our best stories to tell our friends are of failure. Success is not entertaining!

BH: In a lot of ways, this is why I love Hamilton. A lot of people love shit talking it and saying it's gross and dirty and I'm like... duh, it’s got life to it though compared to some major cities. And it’s struggling to come up, it feels like a failure but it’s camp.

AM: Every time I walk out my door I feel I witness some sort of old-timey Buster Keaton fiasco acted out in real time

EN: Hamilton is the purest form of camp! Like yeah there’s rats here, and it’s called the armpit of Ontario... that’s homosexuality baby!

Eli Nolet, Alexis Moline, Jessy Kitchen, and Brendan Hendry at the closing reception, Hamilton Artists Inc., November 2021.

Brendan Hendry is a born and raised Hamilton based artist/musician. His collage work blends fragmented, hyper coloured, 70’s/80’s gay porn, together with personal stories and places. Main sources of inspiration throughout his projects range from themes of identity, sex and body politics, self destruction, to nostalgia, and barren landscapes.

Jessy Kitchen is an interdisciplinary artist, primarily working with ceramics. She received her M.F.A. from YorkU. Kitchen’s research explores the emotional and material intersections of grief, identity and objects as intertwined with art and working-class labour. Through research-creation she seeks to address the complexity of relationships between identity, objects and loss. Exploring how visible and invisible aspects of identity are constructed and deconstructed through objects and location, and in particular the home.

Eli Nolet (they/them) is a queer interdisciplinary artist from the occupied territories of the Erie, Neutral, Huron-Wendat, Haudenosaunee, and Mississaugas (otherwise known as hamilton, ontario). Slowly studying at McMaster University towards a B.F.A. in Studio Art, their practice is conceptually focused and questions the binaries of visible/invisible, normative/transgressive.

Review of Morris Fox’s Vestiges and Remains at Artcite Inc.

February 21, 2023, by Imogen Clendinning

Vestiges and Remains, Morris Fox, photo taken by Kristina Bradt

Vestiges and Remains, an exhibition by Morris Fox, is a séance with a haunted Artist-Run Centre’s archive. Fox’s exhibition, presented by Artcite Inc. (Waawiyyatanong/Windsor, ON), invigorates the gallery’s expansive archive, through the creation of new infrared video and images, video-works, and abstract interventions into the archive. The artist collaborates with dusty manuals and board minutes, activating 16mm found footage, old arts publications, and dirty worksuits. A queer artist and new gothicc writer, Fox acts as the ‘Exhibition Programmer,’ exploring the mystical, the poetic, and the utopian potentials of the speculative. Fox activates the Gothic as an aesthetic device; queering the archive and building community through intervention. Vestiges and Remains excavates the gaps in knowledge embedded in archival documents, and the trauma of those absences.

The Artcite Inc. gallery has been located in the heart of Windsor’s downtown since the early 90s, and since this time, the organisation has amassed a unique collection of artifacts of the artist-run centre’s history. Stored under the white cube in a dusty basement, what Fox refers to as a crypt, Artcite houses a collection of board minutes, film reels, furniture, TVs and monitors, projectors and various other bits of idiosyncratic ephemera. Artcite’s first mandate and mission was steeped in counter-cultural defiance, and throughout the decades their programming has featured fringe and highly contemporary creative approaches to the creation and circulation of art in Canada. Ultra punk and radical in their approach, Artcite ran a number of events which challenged convention– including site-specific festivals, music events and exhibitions.

On the other hand, Artcite, along with many other organisations, has reckoned with the structural racism which is embedded within the art scene in Canada. BIPOC community members, artists and the Artcite staff have been working to enact new policy and commitments towards an anti-racist approach in both their work and programming. Within this complex context, filled with grey areas and contradictions, Fox begins to sift through the archive.

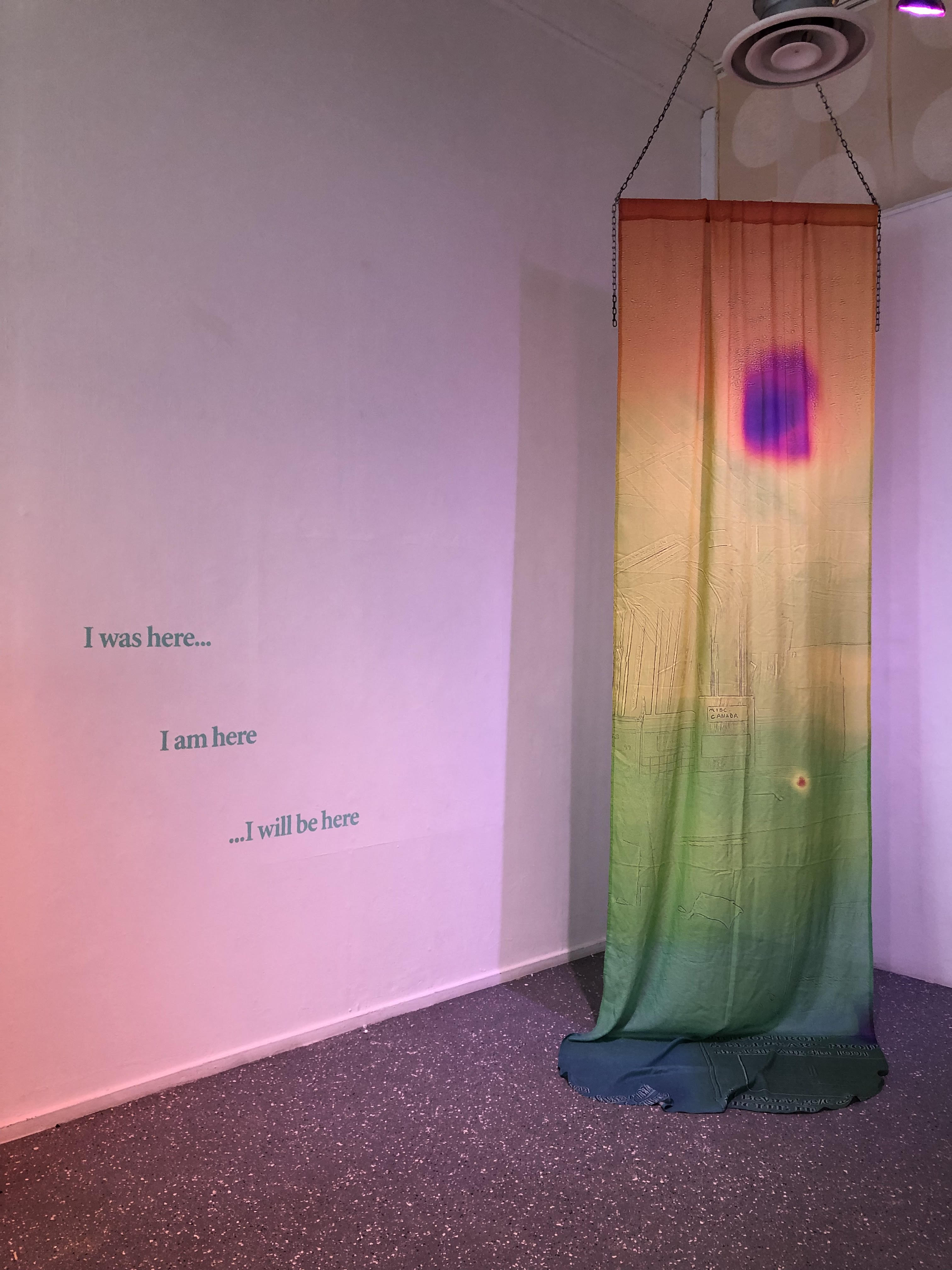

shroud, Morris Fox, thermal imaging and textile sculpture, January 2022

Fox says of Vestiges and Remains, the exhibition “explore[s] the haunted temperature of archives, community memories and the ghosts of labour.” Fox’s works encourage reflections on the nature of an artist-run centre’s archive as both a theoretical form of constructing time, and a tangible record of the past. For Vestiges, Fox created a series of assemblages of objects and materials from Artcite’s basement, textile sculptures featuring thermal imaging video taken in the archive, three channels of video-works, and a sound piece which plays throughout the gallery space. Fox also staged a number of areas where visitors could sit and look through archival materials and his own research.

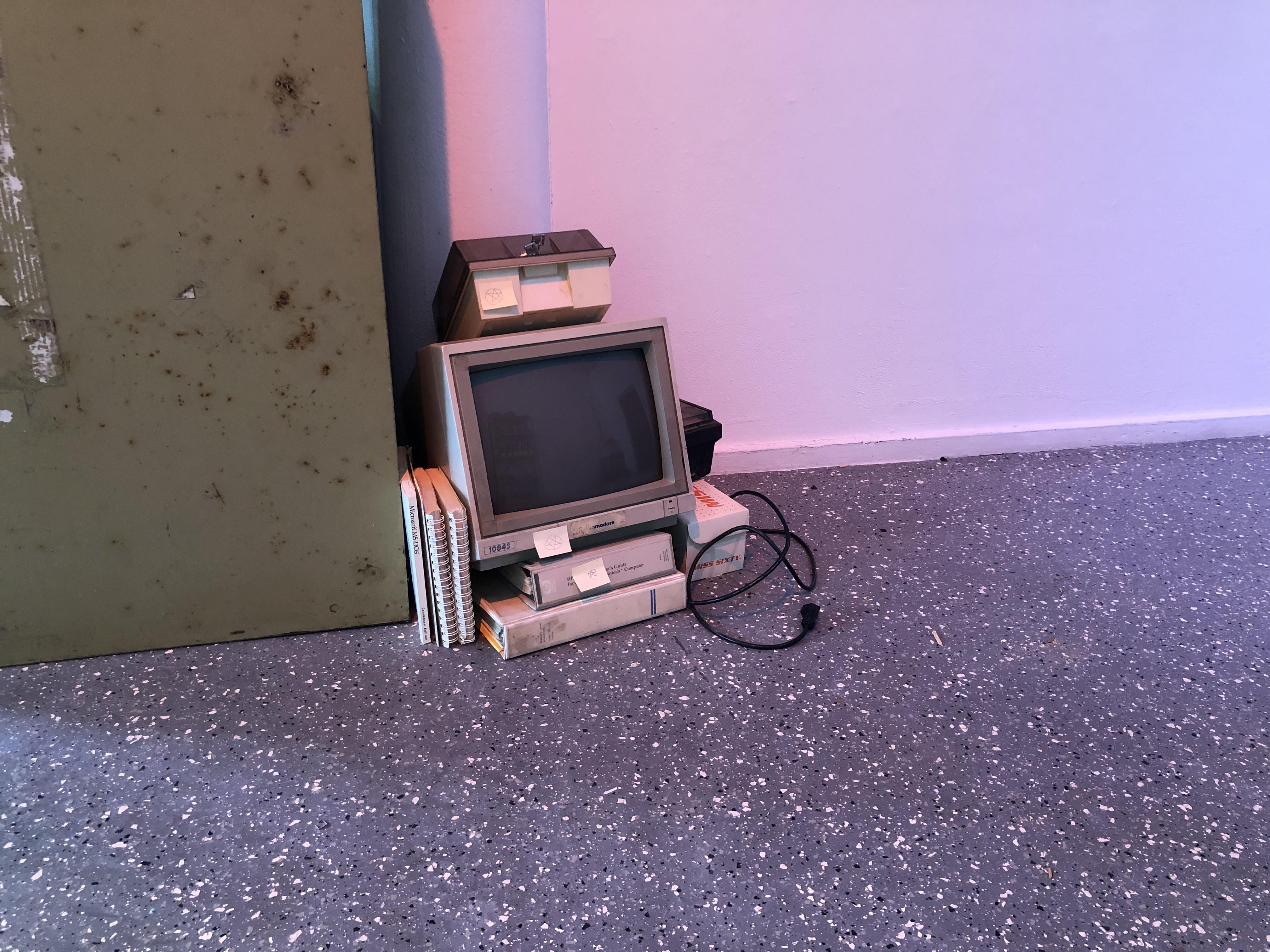

Mood and lighting play a key role in setting the tone for Fox’s installation. The objects in the gallery are refracting light in purples, greens and yellows through the light installation Rainbow’s End. The sound-piece Ghost Transmissions murmurs in the distance, and the exhibition is laid out in such a way that intimate pockets of experience abound; the urge to explore is inevitable. Textile sculptures hang from above the viewer’s head. Objects from Artcite’s dusty basement are delicately juxtaposed, including a Commodore computer monitor on the floor, a floppy disk case and printer manuals stacked on top of it. Meticulously staged, these assemblages allow the visitor to consider how objects transform through time in a poetic state of becoming.

archive cairn, Morris Fox, found object assemblage, January 2022

Throughout the exhibition, the viewer can recognize The Gothic in Fox’s language and aesthetic framing. In the sound piece Ghost Transmissions, there are references to the séance, the crypt, ghosts and mediums, and the reanimation of objects from the Artcite basement - which Fox purposefully kept dusty to allude to their former life buried underground.

In my interview with Fox, he describes the relationship between queerness, The Gothic and the archive as being connected through hauntings,

“The haunting of identities, and objects which keep on coming back, the ghosts that are saying “We are here, pay attention to us.” That’s important. And it’s differentiated from trauma for example. Traumatic history, the experience of trauma is something that repeats continuously until it's healed. Whereas haunting is a bit more ambiguous within its role and also the feeling that we have with it.”