Brown Food

January 8, 2024 by Steacy Easton

On Stephen Shore’s American Surfaces 50th Anniversary, and the 1st anniversary of my father’s death.

For Richard

Stephen Shore, Clovis, New Mexico, June 1972 (source)

- It’s the fiftieth anniversary of the photographer Stephen Shore’s monumental experiment, where he traveled through America, shooting the most banal shit —things he ate, cars he saw, hairdressers, auto mechanics, greyhound stations. When he was in Amarillo he shot ten photos which he made postcards out of. He had them printed by Dexter Printers of America, whose minimum order was 5600 copies. This distinction between art print and commercial photographs means that looking at his prints, books, and eventually digital archives (on museum websites, on Tumblr, and eventually on Instagram) was divided into work suitable for postcards and work not.

- The British photographer Martin Parr had an angrier, more class-oriented version of Shore’s blank eye, compiling a collection of postcards in the UK, erasing the difference between art shot and commercial shot, via an act of curating. In the mid-1960s to early 1970s it was possible for everything to be a postcard and everything could be art. The Shore postcards are in the collection of the British Museum and the Met. Shore says he didn’t sell a single one in 1973.

- Here are some things that Shore shot in Amarillo that didn’t sell: Doug's Bar B Q No. 1, 3313 S. Georgia, Civic Center, 3rd & Buchanan, American National Bank Building, 7th & Tyler, Double Dip, St. Anthony's Hospital, 735 N. Polk, Fenley's Cafe, 322 W. 3rd, Capitol Hotel, 401 S. Pierce, Feferman's Army Navy Store, 201 E. 4th, Potter County Courthouse, Betw. 5th & 6th on Taylor, Polk Street. The buildings depicted are a mix of institutional and vernacular architecture, a mixture of very new buildings and ones more than a century old, brick and concrete. The postcards do sell now, three thousand dollars for three at Heritage Auction last year, framed and authenticated. The Double Dip is still mostly known for Shore’s photo, the BBQ joint is going strong in the same building. People get sick in the hospital, people do uncivil things in the civic building.

- Art is a failed photograph. A photograph is meant to be polysemic—the photographs of Amarillo turned into postcards turn the monosemic quality of art into the polysemic quality of public aesthetic. In a museum art is only art; in the wild it is a souvenir, a placekeeper, a vernacular object, a note on geography, a note on desires (a desire to sell, a desire for this project to be seen, to pay the rent). It fails at all of the things it can be and it only retains one benefit–it becomes art.

- Currently there is an exhibition of Wolfgang Tillmans’s photographs at the Art Gallery of Ontario. There are hundreds of photographs in that show, from tiny 4x6” prints to work five feet tall. Some of the photographs are framed, some are taped to the wall, some are placed in vitrines with supporting material. There are exquisite prints in the show–but mostly they show the artifacts of their creation, a set of xeroxes in collapsing, smeared grey tones, in the slightly dull colours of commercial coupler prints. Tillmans moves the photos around in the show, and there are reproductions–in one room a Xerox print of a man falling from a cliff (falling/diving) on a piece of A4, in another room the same shot a dozen times bigger.

![]()

Wolfgang Tillmans, Natura morta, 2001 (source)

- The work I love most by Tillmans are the still lives, often on a windowsill, often beautifully lit–titled things like Talbot Road (1991–mostly oranges) or Osaka (2004, two exquisite apples wrapped in paper and honeycomb styrofoam) or New York (2001, film canisters, tubers, orange peels) or Calama (2012, avocados and melons in green plastic grocery bags). I was here, and I ate things, and I took photos of what I ate, and I left the place. The rot of the fruit, like the 18th century Dutch still lives. I keep thinking of Rachel Ruysch’s Fruit and Insects from 1711. To be rich enough to let things rot. To be rich enough to make the rotting things allegories of our own rotting. In Shore and in Tillmans some things do not seem to be able to rot. Vanitas and vanity. The Ruysch is in the Uffizi, the postcards are in the Met, the Tillmans are printed by expensive publishers, and show up everywhere. We say Tillmans made these shots, made these installations, the fruit, and the still life exemplary of travel, but were there phone calls, zoom calls?

- The more ephemeral a thing appears to be, the more infrastructure which exists to create it. Like capital, the museum perpetuates itself. The melons still look ripe, as do Ruysch's peaches. The photos of Shore in the 1970s, of mostly brown food and mostly brown landscapes, are the beginning of a new supply slide, and maybe a new middle class. I am eating a peach while writing this.

- When my father took photos, he did not take still lives, but in the last years of his life, there was a panic to travel, to shoot, to make beautiful pictures. An anxiety about the rot. It is unfashionable to admit that we are careful about printing like my dad was careful. I was embarrassed by my father, by his photographs, by the giant print he made of Irish seas and framed awkwardly and gave to my mother. It was a sentimental shot not out of the 19th century–but there is no false modesty to it. The first time I saw the Tillmans show, there was a large, formal portrait of one of Fassbinder’s muses, who aged into respectability. My father was taught to be respectable and re-feralized himself.

- I often wonder if a picture in a book is different from a picture in a show than a picture online. I often wonder if a picture on Pinterest, Tumblr, or Instagram is different from a picture on the museum website. In this age of the digital, in a world anxious about prints, the only thing that exists in image making is the metadata. I do not have my father’s negatives, or his SD cards, or his camera. I have five of his novels, stained by tobacco and coffee, on a shelf. Its own decay, its own brown food. I have not read them. They are formalist, materialist objects.

- Doing provenance for either Tillmans or Shore would be a nightmare. I took my copies of their books from my libraries, books from Steidl or Distributed Art Press, catalogs from shows in New York or Europe. The still lives aren’t really there.

- It seems like a very foolish exercise–to say that this image is 86.9 percent art, to do the taxonomy of it. Are Balderssai’s paintings about painting more art than the photos he took of oranges flying into the air—does the baggage of the archival strip those oranges of their joy? In 1968, Balderssai painted text on canvas—the text said: “Do You Sense How All the Parts of a Good Picture Are Involved With Each Other, and Not Placed Side by Side. Art is a Creation of the Eye and Can Only Be Hinted at in Words.”

- The best Shore photos are things that are placed side by side. They are still lives, and they are brown still lives. The best Tillmans photos are things placed in vast arrays. They are still lives, and they are colorful still lives.

- It seems strange to me to see these commercial products listed in museum collections, with official-looking acquisition records and notes on media. Not postcards, but “photomechanical prints.” They are also prettier than anything else Shore ever did—those cerulean Texas skies. Which is funny, because Shore’s 1973 work is known for either a po-faced irony or a slight slumming underbelly. Which is funny, because maybe the best thing he ever shot was brown foods: pancakes in Utah; a hamburger in Dallas, chocolate cake in Albuquerque, steak and hashbrowns in the Dakotas. This being the 1970s–the plates, the laminate faux bois tables, the placemats, everything surrounding the food was brown. Brown on Brown on Brown on Brown (sometimes curators in Canadian museums call the large Victorian 19th-century landscapes in their back rooms, “brown paintings,” sometimes antique dealers call the unsellable unfashionable furniture “brown pieces.”)

- Perhaps the masterpiece of this “brown food” category, was a photo he took in Clinton, Oklahoma in June of 1972. One of those tables, two bowls of iceberg lettuce, askew. One which has a large white lump in the middle of it, and one of which has a large reddish beige lump in the middle of it. The reddish beige lump is obviously Thousand Island Dressing, the white might be blue cheese or it might be cottage cheese. I hope that it is cottage cheese because then it could be bookended by a shot Richard Knudsen took of Richard Nixon’s last meal after he resigned; after he flew back to California. The last meal that Nixon ate was cottage cheese, pineapple, and milk, on a tray, that tray on a brown table.

- Cottage cheese is a food of control. It is a food that is defined by what it isn’t–not quite cheese, a diet food, what you eat when you don’t want to eat actual food. It is a white food (entendre intended). One of the defining characteristics of Autism was once considered a white diet. To be accurate, Autistics are known to eat beige foods. There are hundreds of guides on the web, for parents, that try to convince adults to force their Autistic children to eat more than beige food. There are many cruel jokes about chicken tenders and beige food. Maybe that’s why I think of Shore as secretly Autistic–or that there is nothing more Autistic than the endless photos of useless things; maybe the average diet in the midwest in the 1970s, put next to the average Autistic meal in 2022 has some family resemblance. Though that said, the ritual of taking the same shot four or five times a week for decades, regardless of where one is, is in itself the kind of ritualistic behaviour that we could consider Autism. I am not saying Shore or Tillmans were Autistic. I am saying my father was. One of the ways I pretend not to be Autistic is to make my food less beige.

- I am never sure if Shore is documenting, if he is taking notes, if he is making art, if he is taking photographs, if he is mocking fly-over country, or is secretly in love with it–whether his photos of beige foods, via the distancing of an aesthetic, through an act of art making, allow for us to take them seriously. What do we know about the food–we don’t know what it tasted like, what it smelled like, who made it, and what it meant for them to make it. There is a hint–this is what America is, sort of kind of, but unlike the post office, the discourse slides itself into art continually, whether we want it to or not. I am sure what Tillmans is shooting–he is shooting a distant, urbane cosmopolitanism. He is showing his wealth, fat and sleek–like Ruysch’s peaches, like Cuyp’s cows, like Ven Helm’s oranges.

- All of the great art that has been made of Nixon–think of the Phillip Guston drawings, phallic aggression as exhausted pathos; think of the epic opera that the minimalist composer John Adams made–and then this photo, an accidental Shore, but one that fails at populism, at grit—there is no pleasure in either, but there is a weird anthropomorphized bonhomie in the Clinton salads. There is an icy loneliness in Nixon–all he wanted to be was loved, and all he got was two rings of pineapple, cottage cheese, and a single glass of milk.

- I think that the Clinton, OK photo is genius for formal reasons – how the shapes twin and separate, how the composition is slightly off – and for social reasons – because of how it both works with the tradition of still life, as an example of prosperity and upends it; I love it because of that slightly snobbish response–I can make art out of anything, I can make art out of the most banal commercial shit; I love it for sentimental reasons because it reminds me of my dad–though my dad thought he was above sentimentality.

![]()

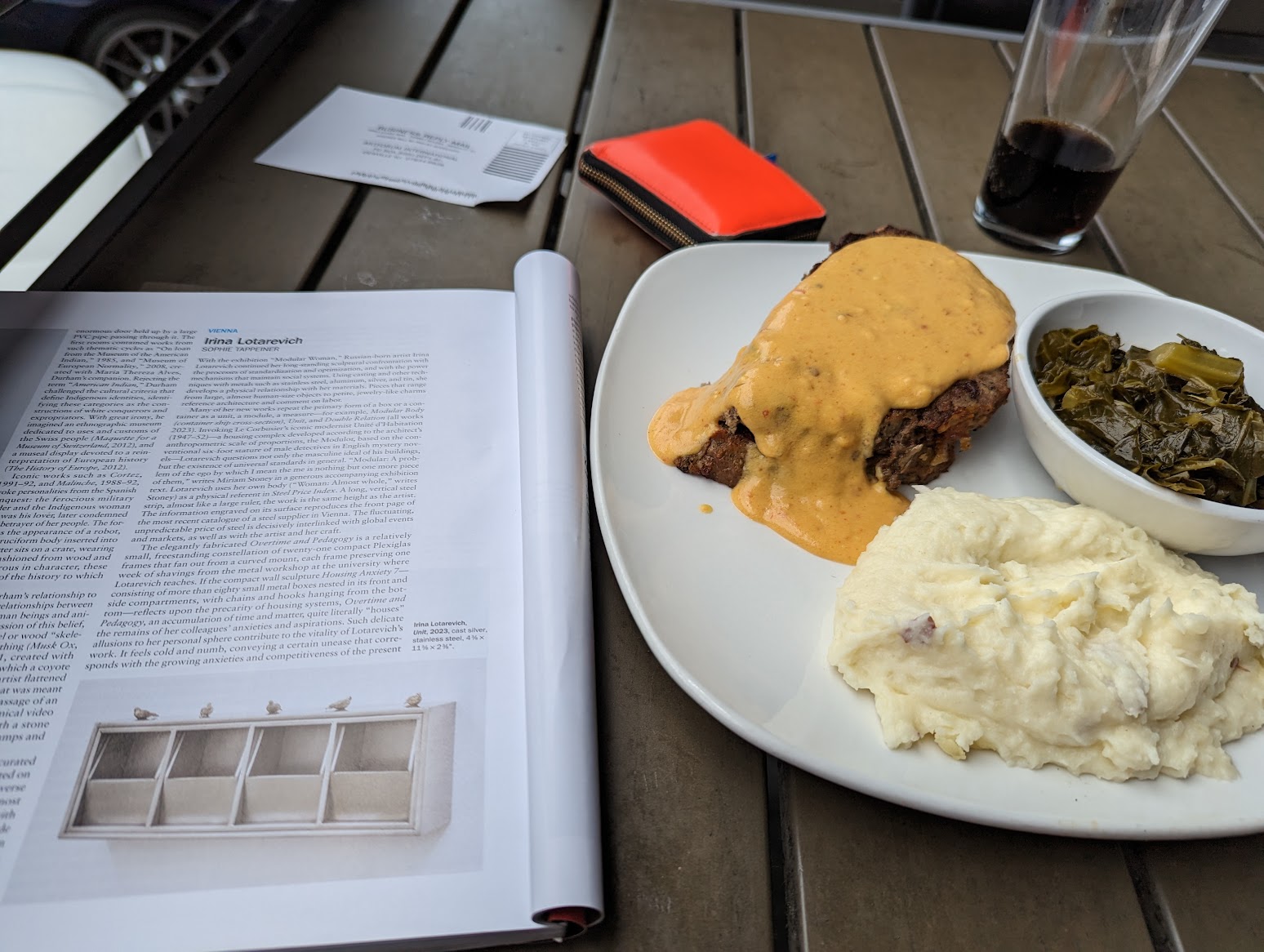

Photo courtesy of Steacy Easton

- I went through the South on a book tour last spring. I ate some beige food and took some pictures, but the pictures and the beige food I ate were not because I was Autistic, but because I was Aesthetic, because I had been poisoned by irony. (Though the queerness of a Waffle House at 3 am was a refuge.) The beige food I eat at home, naked in bed, not wanting to cook, barely wanting to eat–that food I do not document, that is more monosemic. The beige food I take photos of is aesthetic, is monosemic. The beige food I eat privately–encased in codes of quick pleasure, of shame, of desire, of labor and leisure, is polysemic.

- My dad was Autistic and made sure that no one knew it. He was awkward, and he was difficult. His life was haunted by brown foods, and by the 1970s, he also really hated Nixon—like he was progressive in the 1970s, and he never stopped, but also there were more current politicians that he could get angry at.

- I think of my father as Autistic. I out my father as Autistic because of his diet, of burnt carbs, thick gravies, the exacting way that he ordered his Big Macs. I think about his gait. About how he yelled when he didn’t get his way. About the blowouts. About how he kept being fired. But, also, with regard to his generation, the shape of Autism is erased, how we know about his thinking and his process is less about the novels he left, about his photographs, and more about the absence, which limns the edge of human experiences. I never really thought of Dad as Autistic, until he told me, just as Mom got really sick.

- When my dad was six, he was sent alone on a bus to a child psychologist in Edmonton with a peanut butter sandwich in a new and expensive Tupperware container. Dad dropped the container and it got crushed by a truck. (Shore shot in Bozeman in 1973, and he was in Medicine Hat in 1974, so he got close to Calgary, but I don’t know if he actually shot there, my dad would have been in University at the time). Dad survived before he married my mom on Puritan canned stew, the equivalent of Dinty Moore. Before he got sober, my dad drank O'Keefe Extra Old Stock beer–brown label on brown bottle (Douglas Coupland in his book on design and Canada, claimed that he designed the label). The only ethnic food my dad ate was prairie Chinese, which was mostly brown. He would eat twice a week at a small town diner called Uncle John’s where he would order perogies (brown) or a hamburger (browner). My dad cooked a little, but his best dishes were a pear cake (canned pears) and cornbread and chili–all brown. My dad would go out to Boston Pizza and have spaghetti with meat sauce and three meatballs, brown overwhelming the red of the sauce.

- As he got older, he ate less and less–less variety, less colour and less cooking. I see the photos that Shore took, and I see my dad’s diet, and I think about how identity can center on brown foods. I think about my dad being dead for a year, and these Shore photos being fifty years old, and I think about the meals that we ate when Dad traveled. I feel a twinge of shame, that I am again aestheticizing my father instead of trying to understand him.

- When his mother died, my dad took a room at the Coliseum Inn; I checked in on him. He was very drunk on institutionally crafted cheap amber lager, in a room which had not been updated since 1973. Shore would never allow himself such pathos, but it was that kind of play of brown foods, and brown surfaces, that marked a profound grief, which made Dad’s diet make a little sense. My grandmother was a very good cook, she had almost no brown foods in her house–they were not chic. Her only salad dressing was a simple vinaigrette.

![]()

Photo courtesy of Steacy Easton

- I took two trips with my dad in the decade before he died. One to the west coast, Tofino, Vancouver, Port Alberni, Victoria. Here is a list of things he would not eat: udon, ramen, pad thai, sushi, sashimi, blackberries, salmon tacos, seaweed, Franco-Japanese cream puffs. The mark of consumption was a mark of class; the insistence on novelty was a power play. Why, when I knew my father took his own pleasure in the Denny’s pancake, did I think I was better? I bought fruit and shot it on the windowsill. I was mirroring Tillmans and dragging Tillmans. Denny’s makes good pancakes. When I look at the food Shore shot, some of it I think was supposed to disgust the viewer–but there becomes an act of nostalgia—what would have been the vanity of rot becomes entirely selling out. This is an old complaint. My mother and my father, separated, never divorced, living in the same small Alberta town for decades, would go to Wal-Mart once a week and eat at McDonald's. They loved each other and loved Wal-Mart. I never shop there, for moral reasons, for aesthetic reasons. I have my Big Macs delivered to me.

- The second trip was to the American South. We hated each other on that trip, and he was paying, so I resented his money even more. I tried to eat everything, he tried to eat nothing. Maybe his tastebuds were fucked from decades of smoking. The fights were mostly about food–how he didn’t want to go to grocery stores, how he didn't want to eat in the restaurants that I wanted to eat in. There is some difference in sitting at a restaurant called Stoney’s in Brunswick, Georgia –a terrible restaurant, on Sunday morning, a cheap church crowd that seemed hostile, trying to eat a salad just on the right side of rancid, with a vat of thousand island dressing next to it; a half-dozen sports bars where he would order a hamburger burned beyond recognition, and then salt it to oblivion, taking out the lettuce and the tomato.

- I think of the plain cheese pizza in a Brunswick, GA hotel room, I think of the bad pub burgers, I think of cheap BBQ in dead chains—I think about how much he loved Ricky’s and Kelsey’s and Denny’s. In the first draft of this essay, I talked to a friend who was reading, and he said–it sounds like you are dragging your dad for his taste. I am. I think that dad had shitty taste. I want people to read this essay, and think about my readings of Shore, the photographs of Shore, and how I am very sophisticated at reading whatever text is in front of me. I think about my dad.

- Dad would not go to the Waffle House with me, because he thought it was unsafe (though maybe he could not navigate the parking lot), and would not take out from them. I got him Taco Bell, which he didn’t eat. Earlier this year, I was back in the South, too long in Asheville, parked right near the Waffle House, which was the wrong kind of brown food. The kinds of places where Shore would have shot his brown food don’t exist anymore. I took some photos in Asheville, but mostly I read and considered and thought, and found community–at 3 am, after the bars had closed, in the brightly lit, bright yellow Waffle House, though the food was brown as anything in 1973.

- It was also a queer space, and for all my liberalism, Dad was not comfortable in queer spaces. He was not comfortable in straight spaces either–he traveled to England, to Scotland, throughout the United States, and Canada, on his own, taking endless photographs. He was losing his eyesight, and as he grew older and more blind, his photographs got worse and worse. He would try to take photos of everything, but never got a phone with a camera. He was big and lumbering, with a giant professional rig, and he would tell stories about getting caught by the police, and being harassed by motorists, which I am sure happened, but I am also sure he exaggerated. He thought he could make money selling prints–but he wanted to be a good photographer, pictoralist, Ansel Adams. We shot together, sometimes, and he never understood what I shot. I never showed him Shore’s brown food.

- When my dad was dying, in a care home owned by the Catholic church, his cousin would bring him Big Macs and milkshakes. He struggled to eat them. The beige food gave him comfort. The image of this thousand island, this blue cheese-laden bland iceberg gives me comfort. The image cannot be eaten.

- On the trip down South, we went to a fine dining restaurant in Savannah, GA. It was in an old ice factory in a heavily gentrified district. I have told this story about how I ordered good food–the risotto, the polenta, and the deconstructed banana pudding. I chose delicate wine to match. Dad would hector the server—he wanted the same kind of spaghetti and meatballs that he got at home. He started the meal talking about how this much food could serve someone for a week, and then he went on checking the server and went on to call me a snob–to say that I had put on airs. Eventually, he got his northern Italian meal in a southern Italian restaurant. The part of the story I don’t usually tell is that I ordered a very expensive glass of rye, to finish the meal. It was contempt rye, it was revenge rye. It was a fuck you to all of that brown food that I secretly loved and that he would only eat.

- I wonder, sometimes, if Shore’s photos from the 1970s, or the appreciation of Shore’s photos now, are like that contempt rye. It seems significant that as Shore got older, as the grants and slick magazines came in, the work got prettier; culminating in a set of photos in Monet’s gardens. The tension there is a tension in taste. The ability to aestheticize working-class meals in working-class towns marks how the critic thinks they are better than the person eating the meal. Though Shore must have eaten this, his photos are endlessly before, and are never after, making the subtle argument that the aesthetic is more important than the eating, the brown is a formal choice–like a Rembrandt gone white trash and then raised from its descension, from the careful eye of a photographer and printer. Did Shore ever eat the Salad? What kind of salad did he eat–the white or the brown?

- When the owner of the small town diner died, and we went to his funeral, and afterwards, we went to the dive bar portion of a Chinese restaurant so bad he wouldn’t eat at it. We drank Jamesons’ neat–I might not have been 18. When he died, I bought a bottle of Michter’s small batch sour mash. I’m drinking a dram now in an Alvar Allto glass. Aren’t I urbane?