Baltrop

April 21, 2020, by Steacy Easton

Photo courtesy of Brandon Canning

1. This year, the Bronx Museum showed dozens of photos by Alvin Baltrop, shot in the late 1970s. Baltrop was hard of hearing, black, and a Jehovah’s Witness. The photos were of the piers--industrial, and underdeveloped, and mostly used for queer recreation.

2. The piers, both the specific ones that Baltrop shot, and others--as far away as Brooklyn, were written about often--in the memoirs of Samuel Delaney (the SF writer), and David Wojnarowicz (artist and novelist), Arthur Hollander, and Tim Dlugos (Poet). They were photographed--again by Wojnarowicz, by Peter Hujar and Larry Fink (who was a mostly closeted lawyer for the New York Department of Transportation). They were intervened with, by performance and installation artists.

3. In her book, Cruising the Dead River: David Wojnarowicz and New York's Ruined Waterfront Fiona Anderson, thinks about life on the piers as “cruising ghosts” ---as the industrial refuge of the buildings, holding bodies in the dark, the work in the shadows. But there is another kind of ghost--I doubt much of the writing happened at the piers, this was not ethnographic research, someone taking notes with pencil in a reporter's notebook.

4. A photograph was taken, as an aide de memoire, and then that photograph, the physical incorporation of the memory, would be developed elsewhere. The history of public and urban sex is the history of actions that occur in the dark, and deveolp a kind of history, told quietly from hand to hand, the ephemerality of the space and the empherality of communication building up into the concreteness of bodies. As George Chauncey notes in Gay New York, the cruising grounds around the water were the result of the police closing more central cruising grounds in the 1960s, because of the presence of the World’s Fair. The sexual utopia that was so well-documented, then, occured in New York, for a little over two decades, from the 1964 World Fair, to the sex panics because of AIDS in the 1980s, and the tearing down of the piers in the mid-80s. Cruising always occurs, the methods and places change.

5. The photos are small enough, and awkward enough, plus knowing Baltrop’s biography, and the recalcitrance of commercial printers to handle these materials, and the popularity of printing work in bathrooms, it would make sense that these prints were domestic, most likely in the bathroom. In the case of Baltrop, the methods and places were set by photographs processed in a tiny bathroom . I wonder what else happened in that bathroom, the room in the house that is the most obsessed with all kinds of bodily containment, a semi-public room, that must be difficult to hide.

6. Baltrop, like Vivian Maier (who also developed in the bathroom), has been returned to us as a kind of folk hero--big museum shows, big coffee table books, careful essays indicating how his photos were about deliberate aesthetic choices as much as anything else. Looking at Baltrop photos--they are often out of focus, they spend as much time on the architecture of the piers as the bodies of sunbathers, they are the backs of people more often than they are the fronts of people--they seem private archives, tender, and maybe a little bit timid.

7. There is this conversation, sometimes about Hujar especially, but about other queer photographers from the 1970s, about being lost, or not being well known. When it comes to Hujar, lost means less famous than Mapplethorpe, but Hujar had the means and the ability to print beautiful shots (see for example the catalog from 1976: Portraits in Life and Death. New York City: Da Capo).

8. Those shots were of people who were semi-famous, or at least famous enough in his scene--a scene that could pretend a kind of demimonde glamour, but had enough money coming in, or at least enough social capital, that no one had to print in bathrooms. There are erotic photos by Hujar, straight ahead, high toned studio work, that are ravishing. His work on the piers is ravishing. The collapse of a sex act on the piers, and the sex act in a studio, the abiliy to aestheticize both, becomes a kind of Ghent Altarpeice of desire. Nominally able to be folded in on itself, nominally able to be carried, but really intended for those whose resources make the carrying a hint of form, more than anything else. This can be carried, but we all know that it doesn’t need to be.

9. Thinking about that social capital--there is this famous photo series of Wojnarowicz (Arthur Rimbaud in New York), taken in and around the piers, of a figure in a Rimbaud mask---Rimbaud on the subway, Rimbaud in Times Square, Rimbaud on Coney Island, Rimbaud pissing (again the bathroom), Rimbaud masturbating, Rimbaud shooting up, Rimbaud on the piers. No matter how broke Wojnarowicz was, and no matter how restless he was, there is this sense of having done the work, the lurid quality of this work amerolited by an obsession with this fin de siecle figure--Rimbaud as hipster, which makes the pleasure seeking another kind of distance--one shared with punks like Richard Hell or Patti Smith.

10. Baltrop’s photos are tiny, less than four by six sometimes. They do not have the arch distance of the studio, they never quote 19th century french poets. They are vest size things, marking a smaller and perhaps more personal ambition.

11. This is why, half way through this essay, I want to talk about my favourite Baltrop--one less about desire, and more about danger, but whose danger seems less performative or hip. Baltrop sometimes shot the graffiti found in these fallen down spaces, but the graffiti was not Haring, or other such luminous figures, and it was rarely skilled. In one photo it is a shot of a room, collapsing, on the left side of the comopositon, a lop-sided, lumpy, drawing of concentric circles, like a target, like a labyrinth, cryptic and unknowing, it seemed ever so slightly ominous.

12. The ominous quality seems real here. Getting to the piers took some amount of work--Delaney, in his “Motion of Light on Water”, talks about mazes of trucks, and stacks of tires, bigger than human scale. Douglas Crimp, the queer theorist, art historian and early proponent of Baltrop’s work, reminds us that there was an elevated highway, waiting to be reconstructed for most of that period, providing a physical impediment---literally marking the territory between the city of New York and the Hudson. This borderland, depending on oral communication, a tiny outland, carved by neglect, assignations noted after the fact, allowed anything to occur.

13. Anything included the conceptual artist Gordon Matta-Clark’s Day’s End where he cut a large circular hole, in the center of a concrete piling, letting light in, making monumental that which was tiny, making public that which was liminally private, marking space in the language of loose affiliations, in ways that seemed monstrously led by ego.

14. I find the tiny photo of the drawing of the concentric circles, even in their awkwardness, lack of scale, their failure as drawings, more poignant than Orzoco’s large, immaculate hole. I find the mostly badly printed photos by Baltrop more poignant than the large scale shots of Hujar. I am worried I am buying into the myth of authenticity.

15. Authentic desire is always suspect. Unmediated desire is always nerve wracking. The men would go to bars near the piers--places like Kellers or the Ramrod, they would get drunk, and they would wander over to the piers. They played working class in the bars they came from, and in the places they ended up--sometimes literally, wearing workwear, the rough trade bars replacing in their own, gentrifying ways, the longshoremen bars that were there before. The mirror of a mirror, the prole fetish replacing actual proles, as much of a queer tradition as fucking in places where people haven’t fucked.

16. But Baltrop mostly took photos during the day, his photos are blazed by direct sunlight. The conversations by theorists and writers of this period were mostly the dark--what dangers held in the day for Baltrop.

17. Then, there was a photo he took of the entrance to an abandoned industrial warehouse, a sheet metal building, semi or truly industrial, maybe twenty feet high. Emblazoned on this entrance, in an almost elegant cursive, was the phrase, “Pick Pocket watch for your wallet – Paradise,”

Steacy Easton, Documentation of Action, Hamilton Tennants League, King Street East 2020

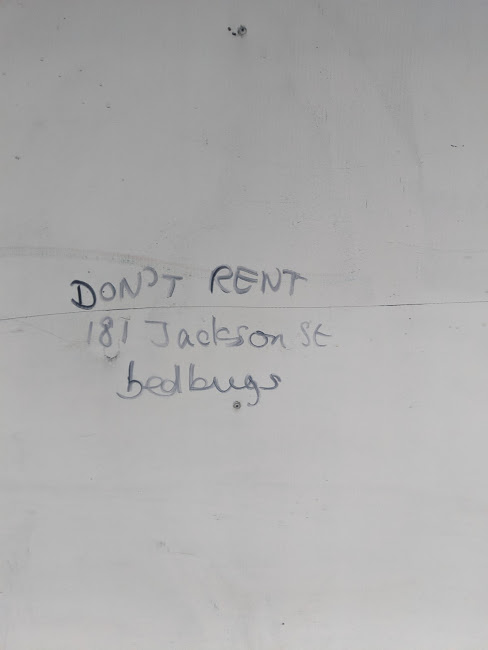

Steacy Easton, Bedbugs (Cladding on James and Hunter), 2019

Steacy Easton, Bedbugs (Cladding on James and Hunter), 2019

18. I don’t know if the title is Crimp’s, another curator--it’s not Baltrop, I don’t think that he titled his work. I would have also titled it, Pick Pocket Paradise, watch for your wallet, but that’s beside the point. I have so many questions--how many pickpockets make a paradise, how do you secure a wallet in the dark, in the midst of sex, how many wallets do you think were lost, is there anything prophylactic that could be done to prevent theives, was this considered just a cost of doing business--this oral tradition of rough trade stealing, or being careful around rough trade, or what my friend, after her stereo was stolen for the third time, in a rapidly devolping neighbourhood in Montreal, a kind of gentrfier’s tax. Who wrote the message--did they bring paint with them, did the message prevent any pickpocketing? Did Baltrop take it as an example of landscape--like he took photos of decrepit piers and the light through holes in roofs or windows? Did he take it after his own wallet was stolen?

19. There is the message of formal graffitti, high art murals, camp reminders of neo-classicism, again the arch irony, the wink and the nod. There is informal graffiti, the scrawl of desire--the important measurements, what one wants, the phone number. There is little documentation of the informal graffiti at the piers--little notation of the ballpoint pen messages, and there is much documentation of large scale graffiti, of those infamous murals. Baltrop’s photos move somewhere between the two, the concentric circles, deliberate and accidental, the message was not quite clear, sort of intimate and imprecise as Baltrop’s printing. But the pickpocket warning--the script has a kind of slumming elegance, the site is well composed, the composition well considered--the warning made aesthetic. This is the space between formal and informal.

20. Though it was an unofficial warning, the pickpocket graffiti had some notion of formal writing--the alliteration between pickpocket and paradise, of course, the aphoristic quality of a paradise for pickpockets--but also how it was written---there was some attempt at a kind of calligraphic loveliness. The question returns to me, how do we aestheticise a warning?

21. This is a question that seems relevant to not only where I am living now, but how I am living now. The ruins that Baltrop, et al photographed, the ruins were accidental--it was people carving lives in the midst of an economic failure, an attempt to create a new social life in the 1970s, economic downtown and sexual liberation working as a singular force. In my hometown, at the grinding crush of an uneven economic recovery, the warning has yet to be aestheticised.

22. There was a baptist church in Hamilton that had existed since the 1890s. A few years ago, everything but the facade was torn down. They were going to build a thirty one story condo tower behind it. This is a very popular movement in Toronto, something called facadism. I don’t know if this is better than the giant modernist elementary school that has been bought by a Condo developer, and has been left to rot. Or the two early 20th century high schools that were left without students, and have not been restored in any real sense. There are also dozens of commercial and apartment spaces that have been bought by the city for an LRT that will never be built. (Each of the buildings bought up has had brightly coloured canning painted over them, marking them as city space, no longer available for people. Brandon Canning’s photographs of King Street and these claddings are instructive here.)

Photo courtesy of Brandon Canning

Photo courtesy of Brandon Canning23. I have not been at the high schools that have yet to be torn down, I don’t know what decadence occurs in them. They are working class spaces, and we don’t imagine that they are working class spaces--they are outside of a middle class imaginary. I don’t think that work will be made from the ruins, in the same way that Hujar or Wojnarowicz made work from the ruins. There is not even a Baltrop of Delta High School, no well composed photographs of either the informal or formal graffiti that Hamilton is constructed by.

24. I keep thinking of the facade on the baptist church. This failed condo tower, this kind of tottering example of our own collapse. There have been formal interventions and informal interventions. A Vietnamese student group hung lanterns on the cladding for New Year's, and for most of two months, you walked through this tunnel of red and gold. There was a wheat paste mural of waterfalls and tigers, for a while, that peeled and rotted. There were endless tags, and then when the developer got sick of the tags, there was an actual official graffiti wall--which is its own parody.

25. There is one piece of graffiti, poignant and artless, that keeps being written on the cladding outside of the facade. It’s the same handwriting, and it has an address--often public housing, a complaint about that housing, often bed bugs, and an exhortation not to move there. It is done in black sharpie, a small notice against an expanse of white wall. The tigers are gone and the lanterns are gone, and the official developers graffiti wall is gone, and they pay enough attention to whitewash the wall, and so every two weeks or so you see a little notice, about bed bugs and city housing and not moving there.

26. One of the things that is lost with cruising, is that it can be classless--one of the things that Delaney notices in his memoirs of sex, maybe a little bit optimistcally, is that with the piers, there was a certain amount of class mingling. There were people who were playing at working class professions, but also people didn’t ask for credentials when hitting on each other. The language of desire was so narrow, and so explicit, that other efforts--at least in that moment were lessened. The sexual networks and the social networks of the poor, overlapped--the whisper networks, informal oral gossip, the note of where to find a place, what is safe and what is dangerous--warnings unaestheticised had a similar space. The sexual networks now require a cell phone, and a data plan, and real estate--the constant question, is can you host, and those who cannot host, are sloughed off.

27. I think about the ruinous church, and the buildings bought and left to rot, and I think of the little hand writing about bed bugs. I think of how we communicated, and what is left when that communication disappears. Walking from the center east of Hamilton, downtown, I walk by the shell of a house that has been burnt down. The house held one of the last remaining Single Residency Occupancy houses, now its own ruin, left undocumented. I think of the houses with strangers gathered in run down houses, that I saw when I was looking for housing in September, and how little of those networks were documented, how little of it was shot, and how little of it was written about--but maybe I was outside of the networks of communication--I wonder if there is a Baltrop of Hamilton rooming houses.

28. Will we know, before they are torn down. The notice mentions city housing, mostly, so there are public private partnerships that seem to be less vermin heavy. City Housing though takes more than ten years to get into. One of the local facilities, beloved by the media, to be the solution--has a director who tells horror stories about these SROs in churches and at religious conferences. These horror stories about rooms above bars, strip clubs, and those run down rooming houses, raise money for new buildings for people to live. The discourse of the street, has been replaced with the language of the bureaucrat--this is it’s own kind of aestheticization, it’s own kind of warning, made even quieter, by the decade long waiting list, by the narrative of saving the poor, by the problem of taking people’s voices away--of mandatory room checks, and necessary paperwork.

29. There has to be careful not to romanticise, to not remake those Rimbaud photographs, to not put a mask of degeneracy ... not to curate other people’s desires. The literal writing on the wall tells us that the oral networks of working class poverty have a written component, but to preserve those networks, to treat them as a kind of medium, with its own communication, is present and real.

30. The problem with it being present and real, is that it is not for those who are not poor--it is not for those who have the social capital or economic capital to attempt to save. It is making a life, a network of survival, and perhaps thriving, in a world that is hostile, that makes ruins, lets buildings to rot, refuses to house, or build, make silly and temporary decisions--thinking about the formal network, and the informal networks of resistance, thinking about the anonymous person who wrote that gorgeous warning that Baltrop decided to preserve, and the artless notice on the walls of where to avoid vermin, let this be present, refuse to have it collapse into metaphor.

_____________

Steacy Easton is a writer and artist, currently living in Hamilton. They are interested in the intersection between class and sex, and visual cultures outside of traditional designations of “fine art”.

Instagram: @pinkmoose4eva

Twitter: @pinkmoose